Kaitai shinsho and its sources

Note

This post is based on a seminar paper I wrote during my masters. I think the comparision of images - illustrations from the primary sources that have been digitized and made publically available - is something that can do well with the digital medium. It also proposes new attributions.

The paper itself.Introduction

This post examines the illustrations of the Japanese translation of Johann Adam Kulmus’s Anatomischen Tabellen1, Kaitai shinsho (New Book on Anatomy)2, published in 1774. Kaitai shinsho is often hailed in scholarship and in more popular writing as a paradigm-changing event in the field of Rangaku, or Dutch studies, as well as medicine in Tokugawa Japan. Sachs, for example, outright states that ’the study of anatomy with Central European methods began with this translation’3. Sakula describes a memorial erected to the book in Tokyo in 19594. Such concentrated attention and praise is somewhat reminiscent of Skinner’s ’mythology of coherence’ and ’mythology of foreshadowing’5.

Two German articles deal with the Anatomischen Tabellen and Kaitai shinsho in detail, those by Sachs6 and Wagenseil.7 In English, a brief overview is given by Sakula;8 most other scholarship treats it in the context of a bigger topic, such as Low9 or Horiuchi.10 There is one monograph that deals with the subject at hand (Gabor Lukacs’s Kaitai shinsho), however, this has received mixed reviews11.

Brief overview of the history of the translation

Kaitai shinsho was based on the Dutch edition of the German work12, published in 1734 by Geradus Dicten in Amsterdam13. The original Anatomischen Tabellen served as a textbook for students of surgery, which is why it was written in German, with short explanatory texts and many clear illustrations, reaching 23 editions (14 German, 1 Dutch, 1 French and 5 Latin)14. As Santoni15 demonstrates, the Japanese edition wasn’t a precise translation of the Dutch work, with parts like the dedication or the preface missing next to various comments about the Christian context. They omitted the footnotes of the original that contained the long explanations, and some parts reveal their battle for a clear understanding16.

The Japanese translation was published in the form of five bands (257 x 178 mm large, 6-7 mm thick according to Sachs17), four of which are text and one illustration. The latter is composed of a preface by Yoshio Eisho 吉雄永章, Kulmus’s translated foreword, Sugita Genpaku’s 杉田玄白18 foreword, the illustrations (41 plates), as well as an afterword by the artist Odano Naotake 小田野直武19. These have been translated into German and can be found in Wagenseil20.

There exists an oft-cited anecdote detailing the reasons for beginning this translation project. Maeno Ryōtaku 前野良沢21 and Sugita Genpaku witnessed the execution and dissection of a criminal named Aocha Baba in 1771 and compared what they saw with their copy of the Tabellen. The end result was:

Horiuchi argues that a point of emphasis is ’serving their lords’, that is, the Confucian social context of learning being valuable insofar as it serves the state. With the conviction that their current medical knowledge wasn’t the best they could thus provide, the commencement of the translation was a necessity in the Confucian gentlemen paradigm that Sugita and his companions defined themselves by. This emphasis on the utility of the new equaling its worth is also discussed by Kuriyama23 when talking about the Western-style illustrations. Furthermore, this Confucian aspect is further underlined by the end text itself, which was written in kanbun, traditionally associated with the higher classes and the culturally elite.

There were several collaborators, some named much later by Sugita; the group consisted of at least Sugita Genpaku, Maeno Ryōtaku, Nakagawa Jun’an 中川淳庵24, Ishikawa Genjō25, Katsuragawa Hoshū 桂川甫周26, and Odano Naotake. Much has been discussed about Sugita in other literatures, so this post will forgo that27.

Maeno Ryōtaku (1723-1803)28 was of samurai class, and a pupil of Yoshimasu Tōdō (1702-1773) and Aoki Kon’yo (1698-1769). Brought up by a physician uncle, he trained under Yoshimasu and was eventually adopted into the Maeno physician family and succeeded as the head. From Aoki, he began to learn Dutch, which led to two visits to Nagasaki, and Ryōtaku having the best grasp of the language in their translation circle. It is assumed that he didn’t think the translation was ready at the time of its publication, which is why his name was ommitted.

Nakagawa Jun’an (1739-1786)29 was from a physician family, and a pupil of Yasutomi Kiseki, from whom he first learned of western medicine. He had close ties to Hiraga Gennai.

Katsuragawa Hoshū (1751-1809) was from a physician family with interests in Western medicine and topography. He was appointed in 1793 as a teacher at the Igakkan, the medical school of the shogunate, specializing in Western style surgery. According to Goodman30, it was Katsuragawa who procured the government’s sanction for publication.

Odano Naotake (1749-1780)31 was a member of the Akita ranga school of painting. Upon his daimyo’s orders, Odano stayed with Hiraga Gennai in Edo for five years, from whom he learned Western-style painting and book illustration.

In 1774, the preliminary text of Kaitai Yakuzu was published. This served to acquire the approval of the authorities before the publication of the full work.

The illustrations

Printing techniques

Existing literature dealing with Kaitai shinsho often talks about the quality of the images as worse than the originals; by Wagenseil: “Alle Bilder des Kaitai Shinsho sind qualitativ wesentlich schlechter als ihre Vorlagen: ...” (p. 78); by Sachs: "[...] die qualitativ - im Vergleich zu den "holländischen" (eigentliche deutschen) Kupferstichvorlagen - schlechteren Holzschnitte des "Kaitai Shinsho"[...]" (p.81). However, these discussions omit the examination of the fundamental difference between intaglio and that of relief printing.

The Anatomischen Tabellen and almost all other Western anatomical books that rangaku scholars of the age came into contact with used the intaglio technique to create their illustrations. In this process, the reverse image is etched or engraved into a metal plate (usually copper), with the ink remaining in the depressions at the time of printing, from where it transfers onto the paper as the paper is pushed into the cavities by the press.

In contrast, relief printing necessitates that everything but the image be carved down, leaving the higher surface with the ink that is transferred to the paper, often by pressing down with hand. This was the technique utilized in the making of Kaitai shinsho, and all other Japanese books of the age.

This difference in the position of the ink is substantial when it comes to the density of the line and the possibility of details such as shading and crosshatching. Form and depth could be shown through shadows masterfully in intaglio, with very thin and closely drawn lines. This fine line is not possible with the softer woodcuts; in fact, figures are usually depicted in a flat manner, "completely devoid of shading or shadows"32. The Japanese woodblock’s strong suit is its freedom of line, colors, and integration with text.

Despite this technical given, the artist Odano Naotake did try to replicate the use of shadow for depth in many cases. But there was only so far this could be taken in a woodcut; a comparision of Bidloo’s images and those of Kaitai shinsho make it clear that such soft transitions were impossible to achieve, and further addition of the discontinous shadows would have more than likely muddled the clarity of the illustration. This was later achieved with the intaglio print of the book, Jutei Kaitai shinsho.

The etching or intaglio technique as used for illustrations was introduced by Shiba Kōkan33 from 1783. Kornicki writes that this was particulary associated with the Rangaku school’s vision, utilized among other subject matters for medical illustrations34.

To declare these illustrations qualtitatively lesser, despite their precise nature as argued above, is to favor one technique over the other without argument. Of course, it may be argued that the intaglio technique is better suited to medical illustrations, but this assumption begs the question: is it a simple western cultural habit that we associate this technique with classical scientific illustration? What exactly about it is more precise?

Western visual culture has put much emphasis on shadow, light, and form since the Renaissance, when the use of perspective became the leading paradigm of depiction. Since then, the subjects of the illustration are depicted from one viewpoint, as though gazing through a window, with the goal of the artist being the mastery of life-like depiction, the ultimate imitation. The technique of intaglio serves these needs very well; woodblock techniques were quickly sidelined in the repertoire.

This obsession with perspective and form cannot be said for the Japanese context at this time. Movement and clarity was much more important, as demonstrated by Tinios35. Epistemic images of this tradition rely on few lines and annotations within, the merging of text and image to make their points clear.

Sources

Next to the original tables from Kulmus, five works serve as sources of the illustrations. These foreign images are clearly marked with seal script kanjis from one of the five elements, making attribution simpler; although, as Wagenseil36 notes, the authors have been mistakenly named. The following table lists the sources as based on my comparisions.

As clear from above, I propose a different attribution than Wagenseil. Sugita isn’t wrong when he gives Ambroise Paré as a source, as the images of the hand and foot do come from his work, and not from Bidloo’s, as Wagenseil and Sachs both suggest. They also name Coiter as a source, in place of which Wagenseil suggests Vesal(ius), (Sachs merely states the latter as a source). I could find no match to Coiter and Vesal, instead, many images match the work of Valverde, from whom the title page has also been copied. Mestler notes that "the Japanese had no direct knowledge of Vesalius’ work," but that Valverde copied parts of his De Fabrica37. Which parts exactly is not elaborated on.

As visible from the comparison images below, identification of the sources can clearly be made. I propose that Wagenseil makes these mistaken attributions out of the conviction that the images of Kaitai shinsho are of a worse quality (he clearly states this), and thus are also inaccurate. This is not the case. What he mistakes as a change in quality is in fact a change in printing technique, one that necessitates different pictorial techniques (which he admits), but doesn’t mean a lesser understanding of the images or their imprecise copying.

There is only one place where imprecision in copying seems to occur, on page four. The coccyx and the sacrum seem to be at first sight very crude copies of the originals. This doesn’t fit the overall accuracy of the book, and closer inspection reveals that in fact, the designation is false; they are copies from Bartholin, not Valverde.

Comparisions

Valverde

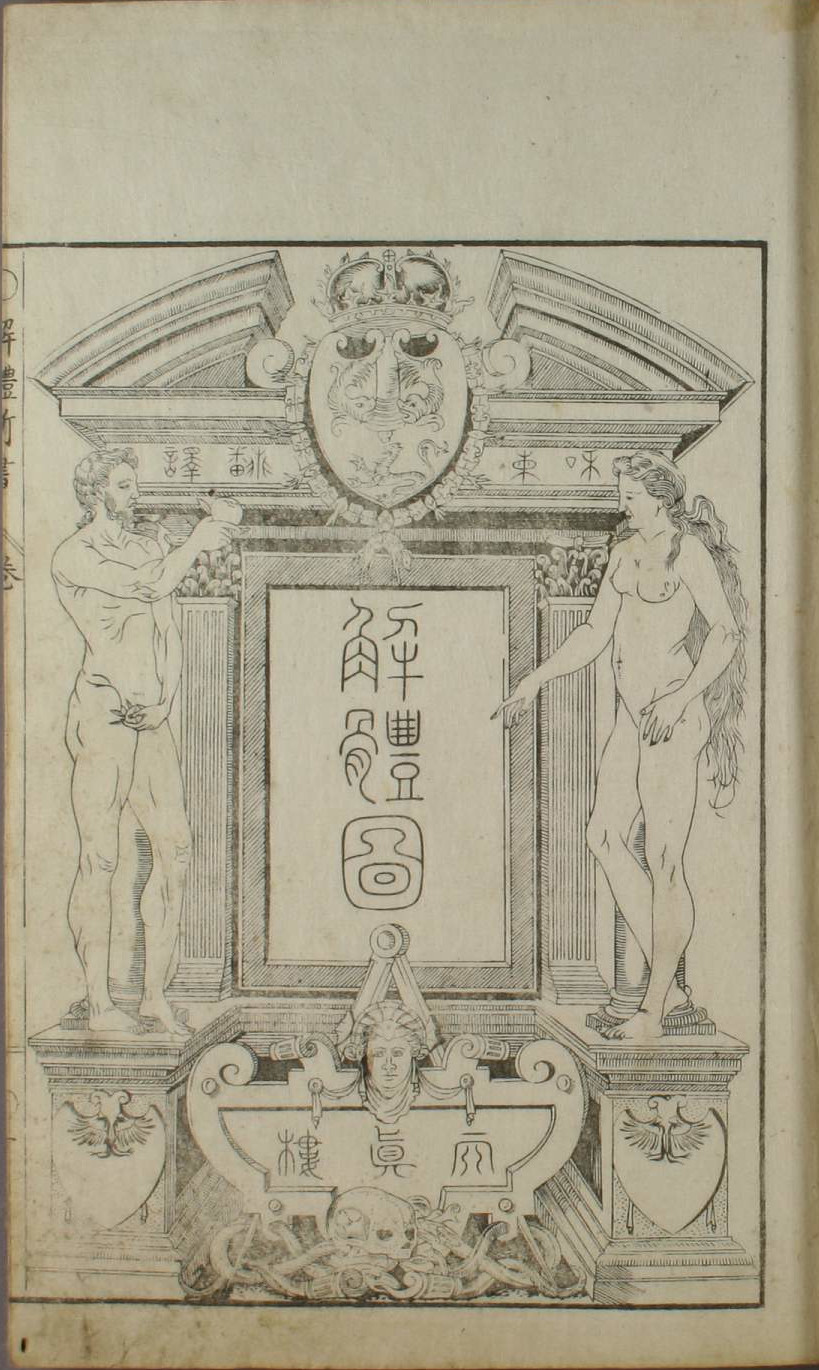

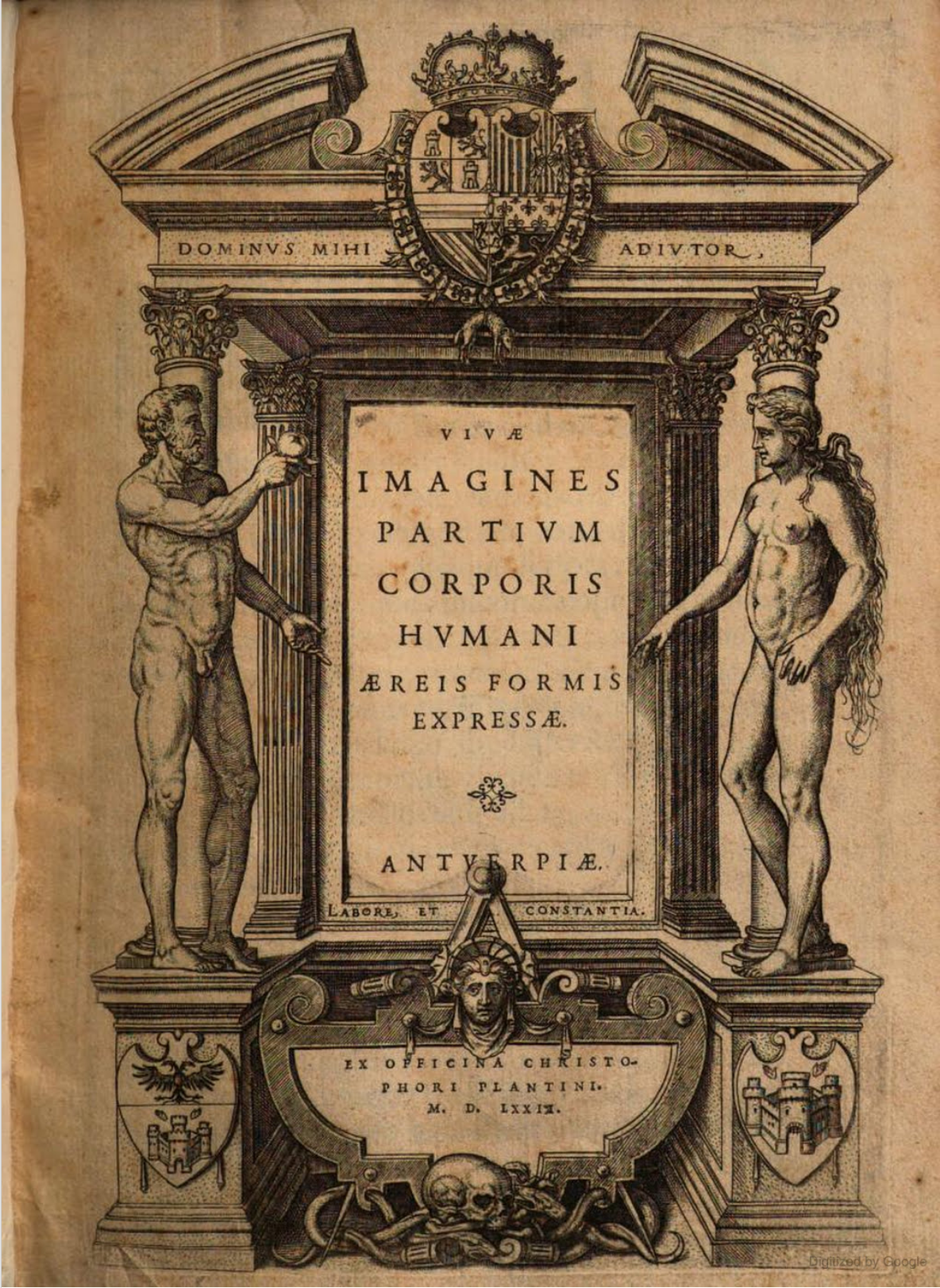

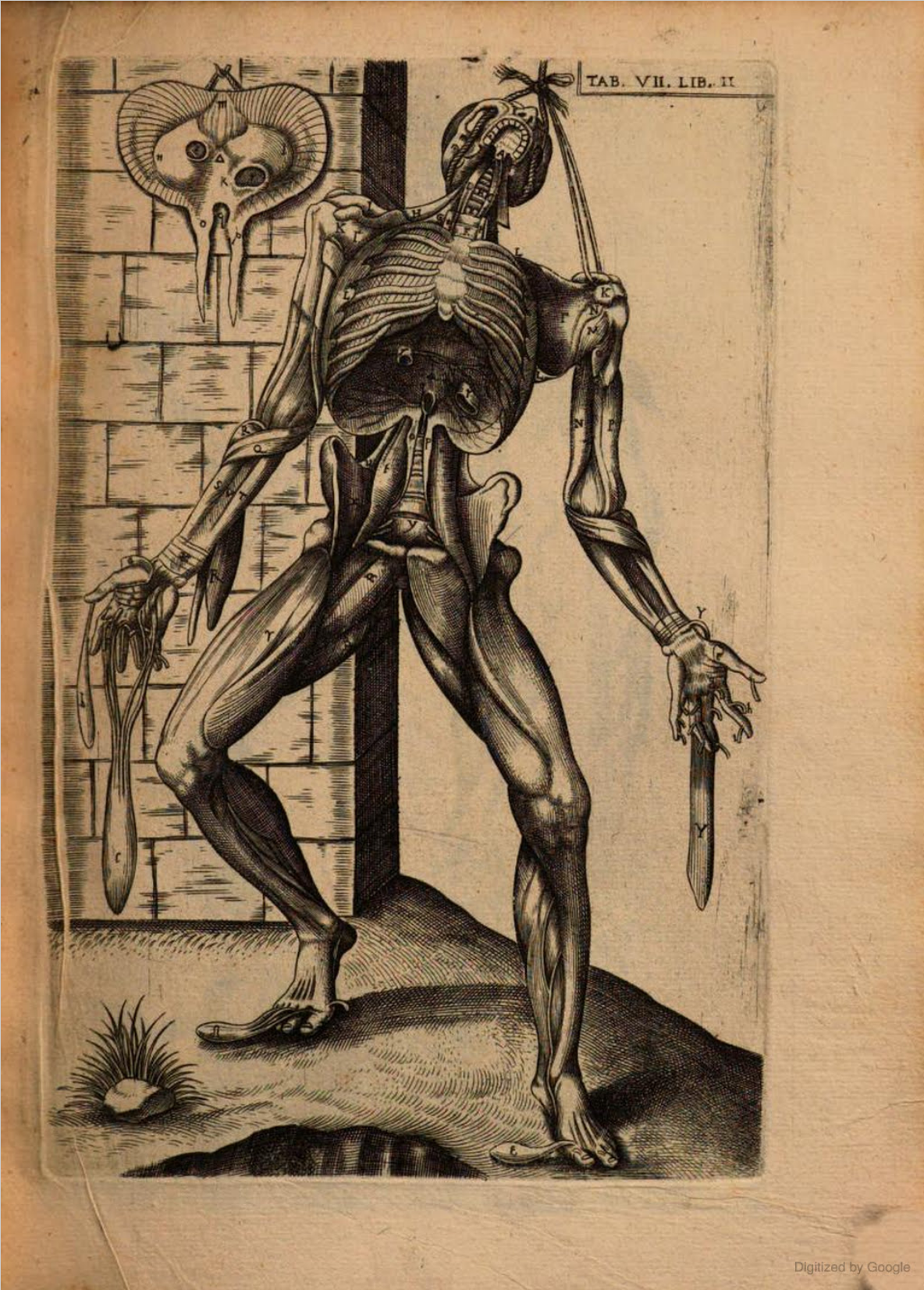

The first illustration in the volume. Note that the position of the man’s left hand has been changed, as well as the front columns omitted in Kaitai shinsho, with an overall reduction in the height of the architectural element.

The title page of Valverde’s work.

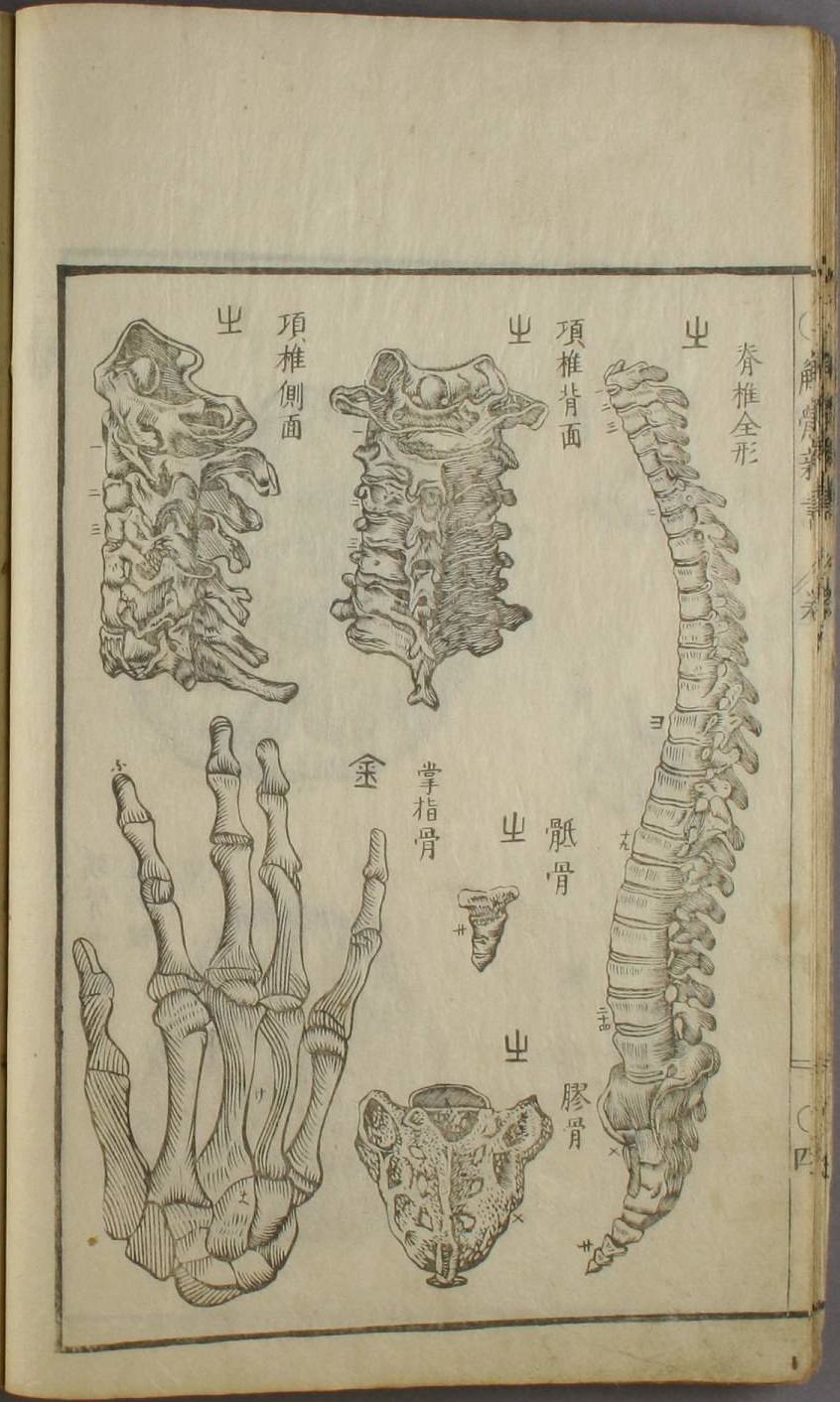

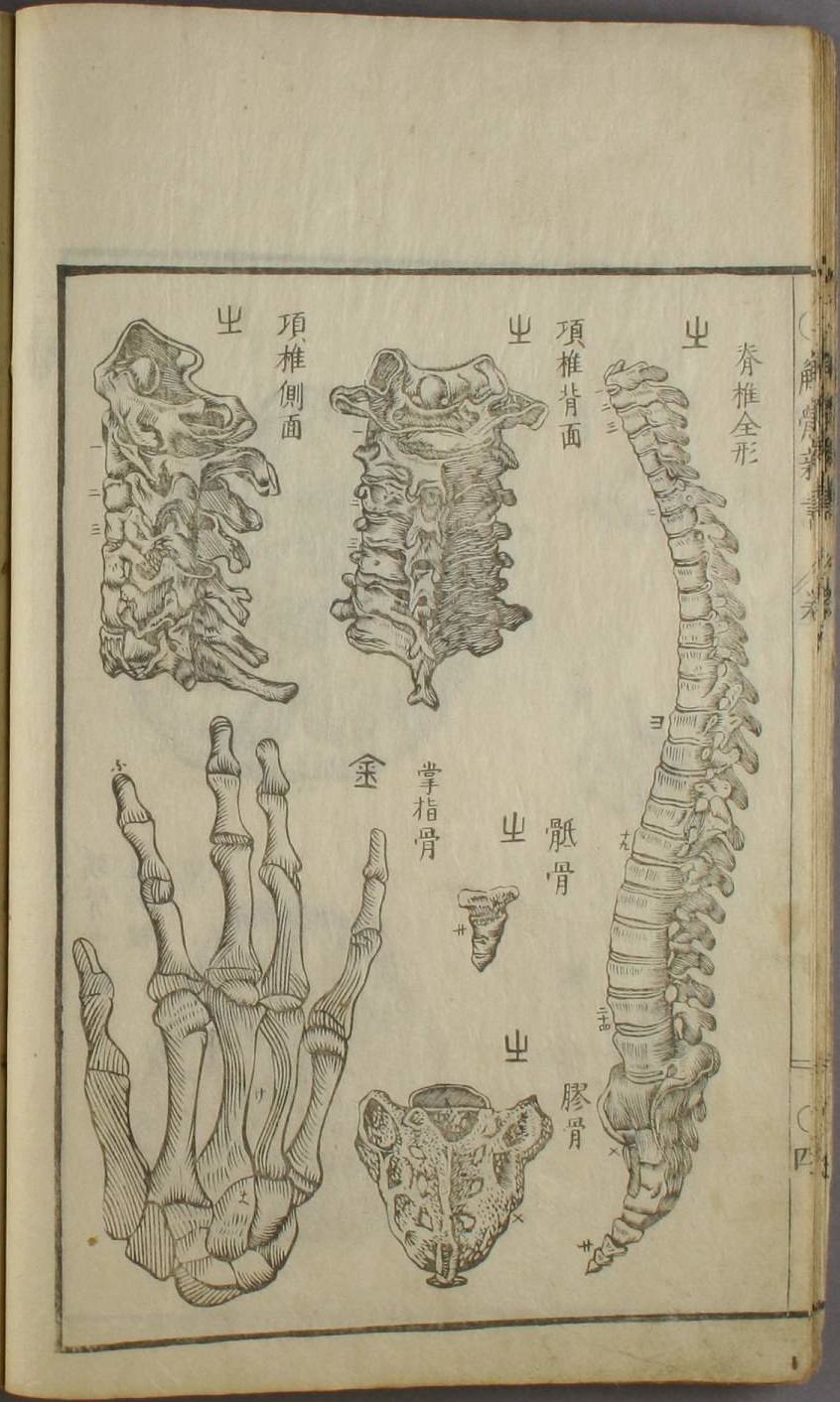

Page four of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. Images marked with the kanji 山 are taken from Valverde’s work. The text reads, from left to right, "the whole form of the spine," "the nape of the neck from the rear,"the nape of the neck in profile," "coccyx*," "sacrum*". The hand is taken from Paré (figure 42), the text reads, "bones of the palm and hand".

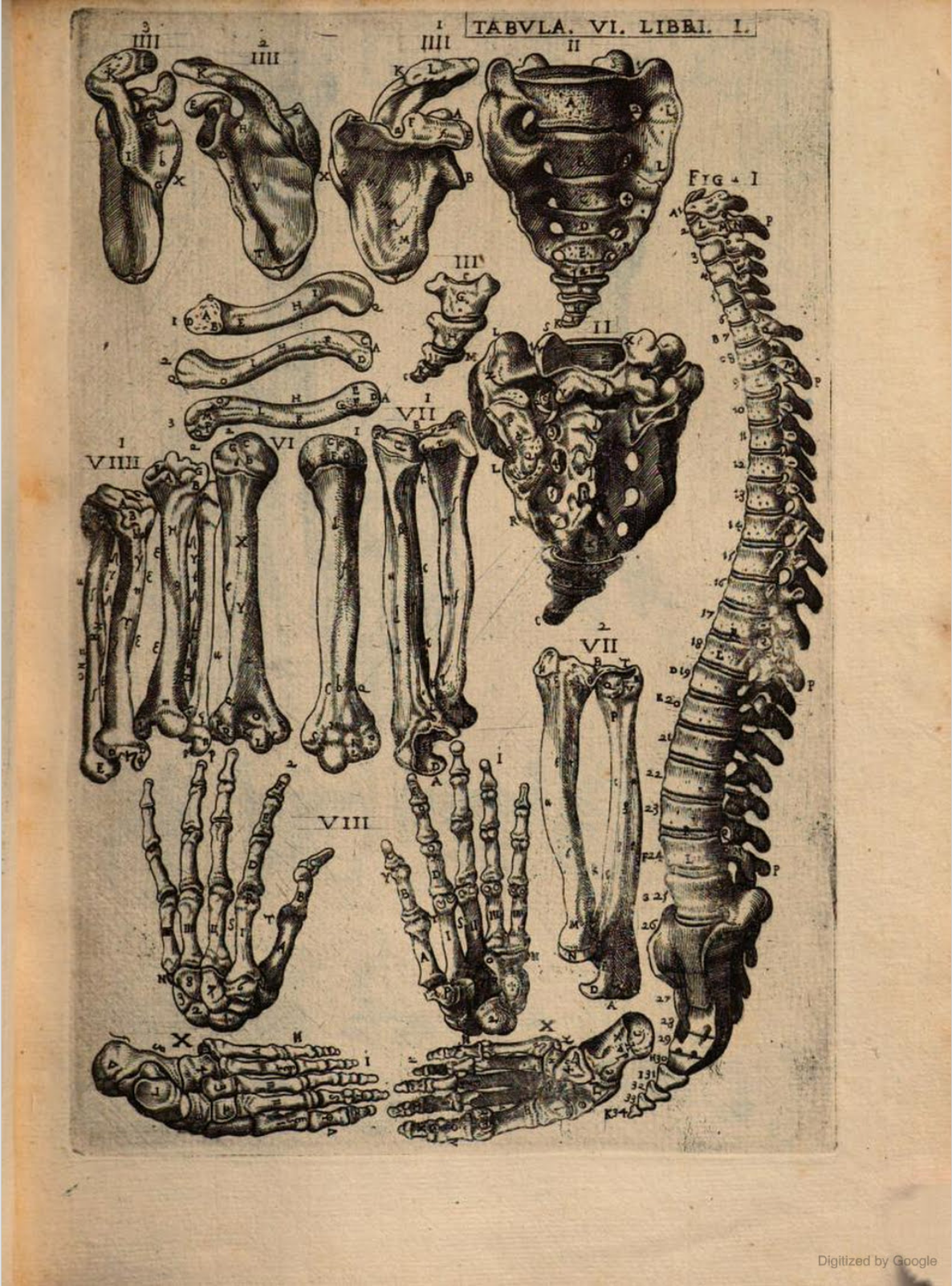

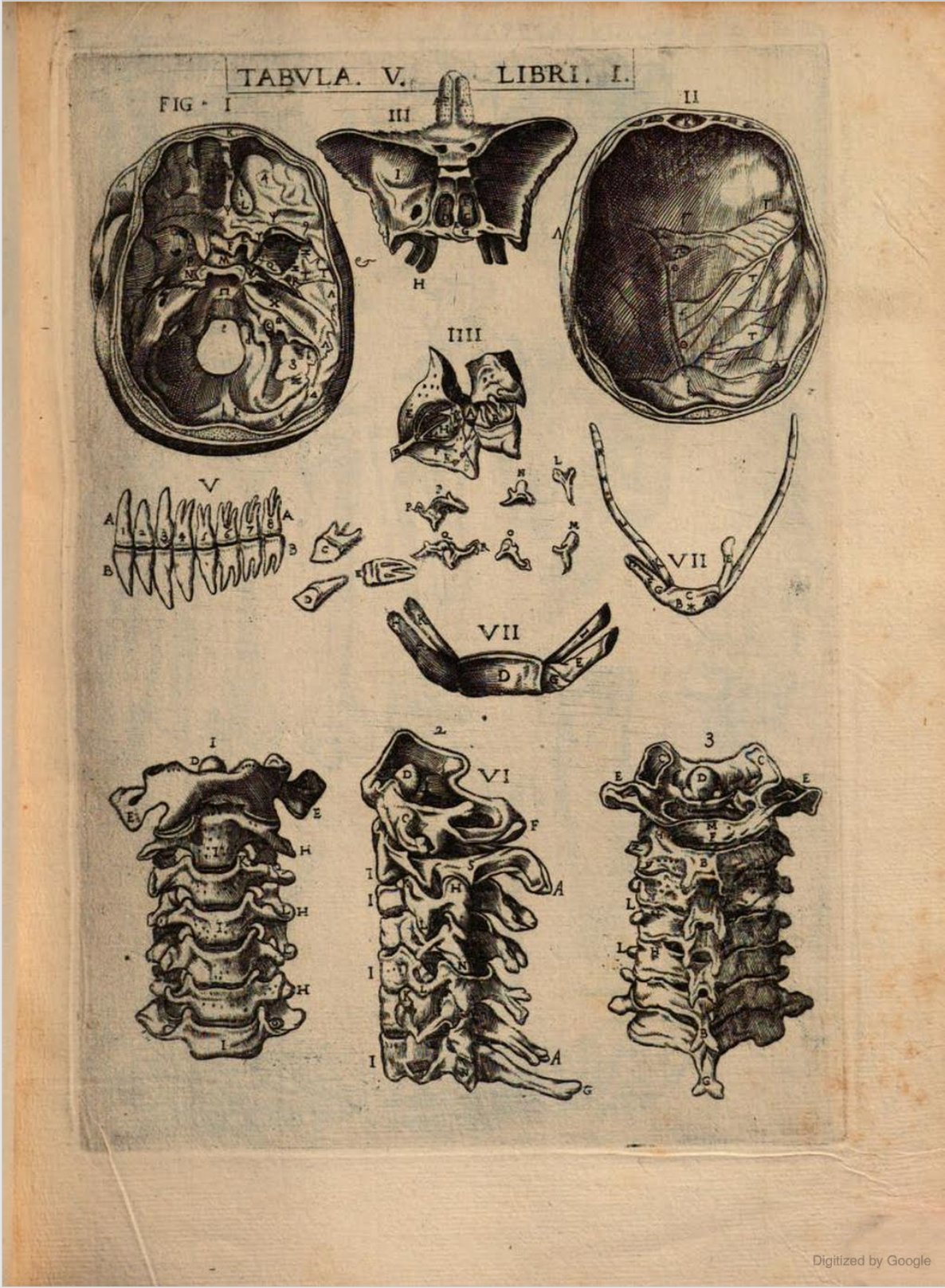

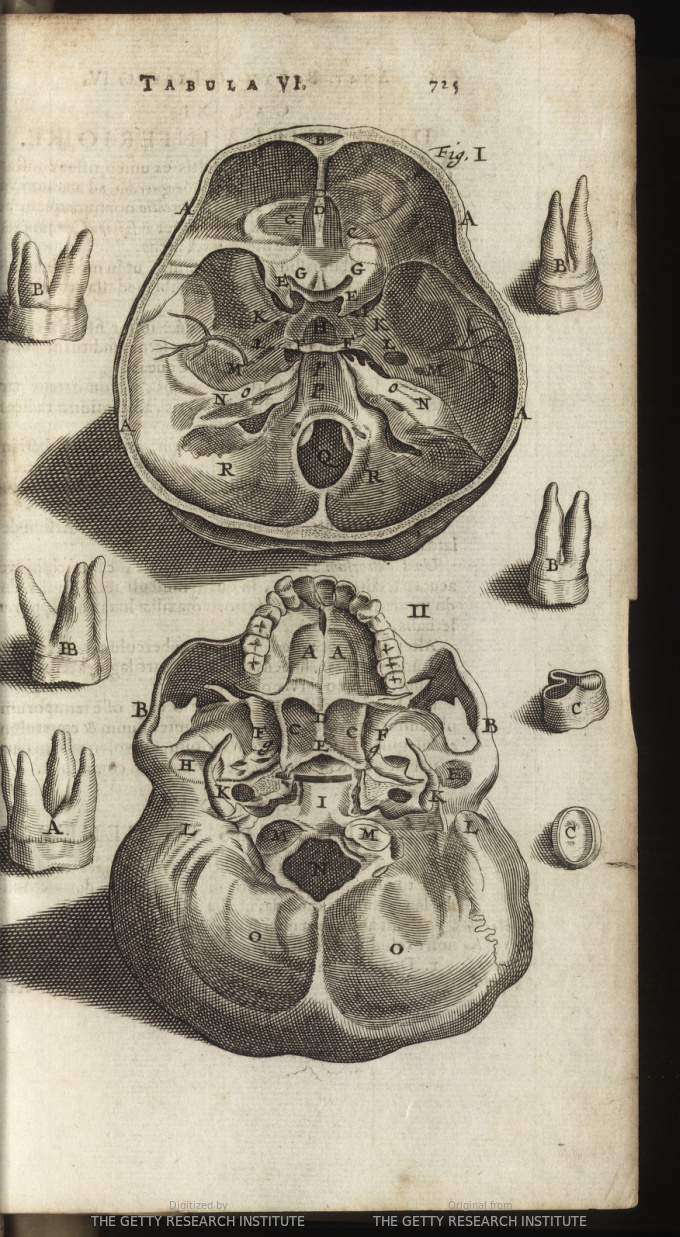

Tabula VI., Libri I. Figure I, II and III are a match, although Figure II and III aren’t as precise copies as others; compared with those in Bartholin’s work (Table 7), it seems more than likely they were wrongly attributed.

Tabula V., Libri I. Number 2 and 3 of Figure VI are a match.

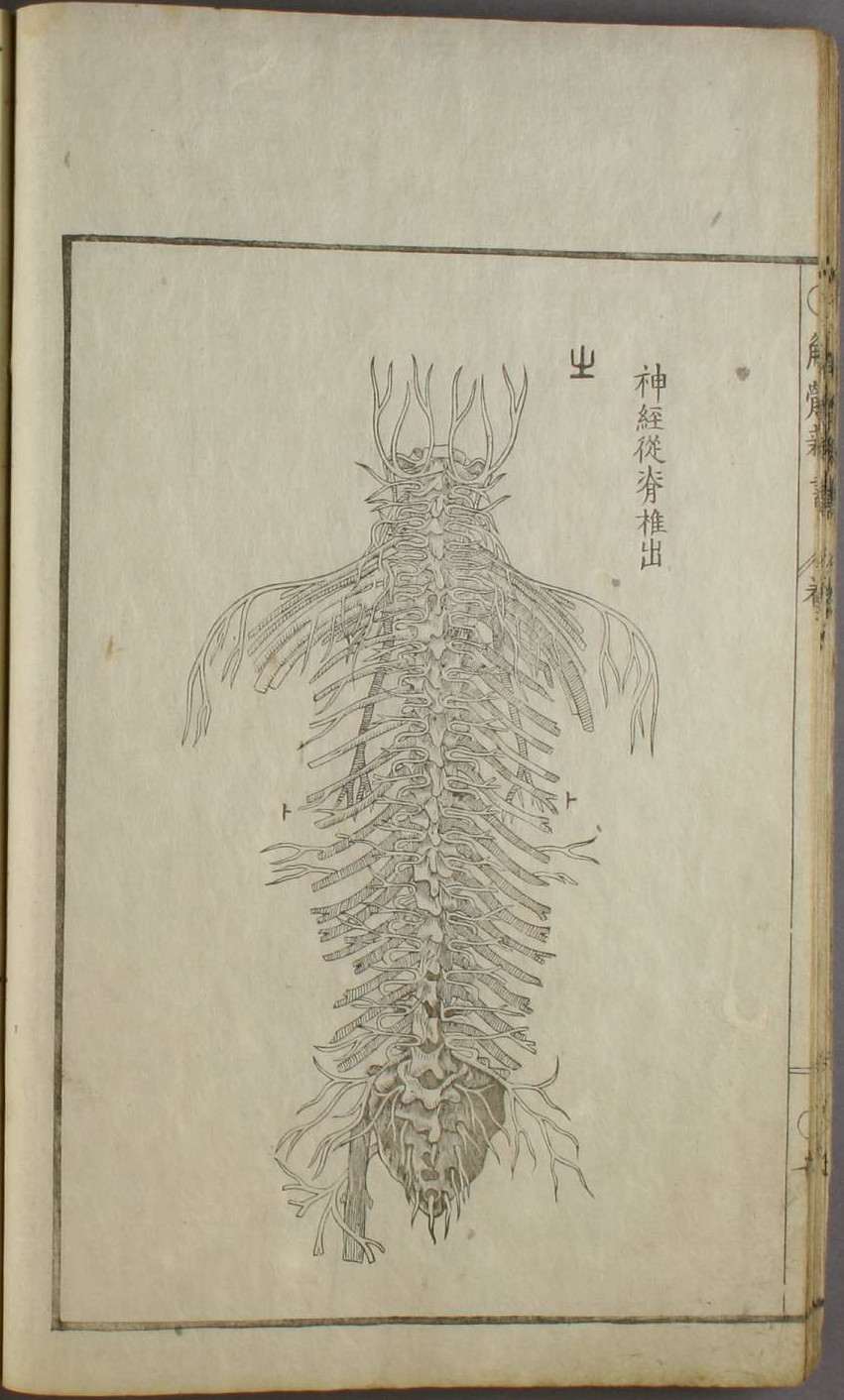

Page seven of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. Text reads, the nervous system accompanying/along the spine.

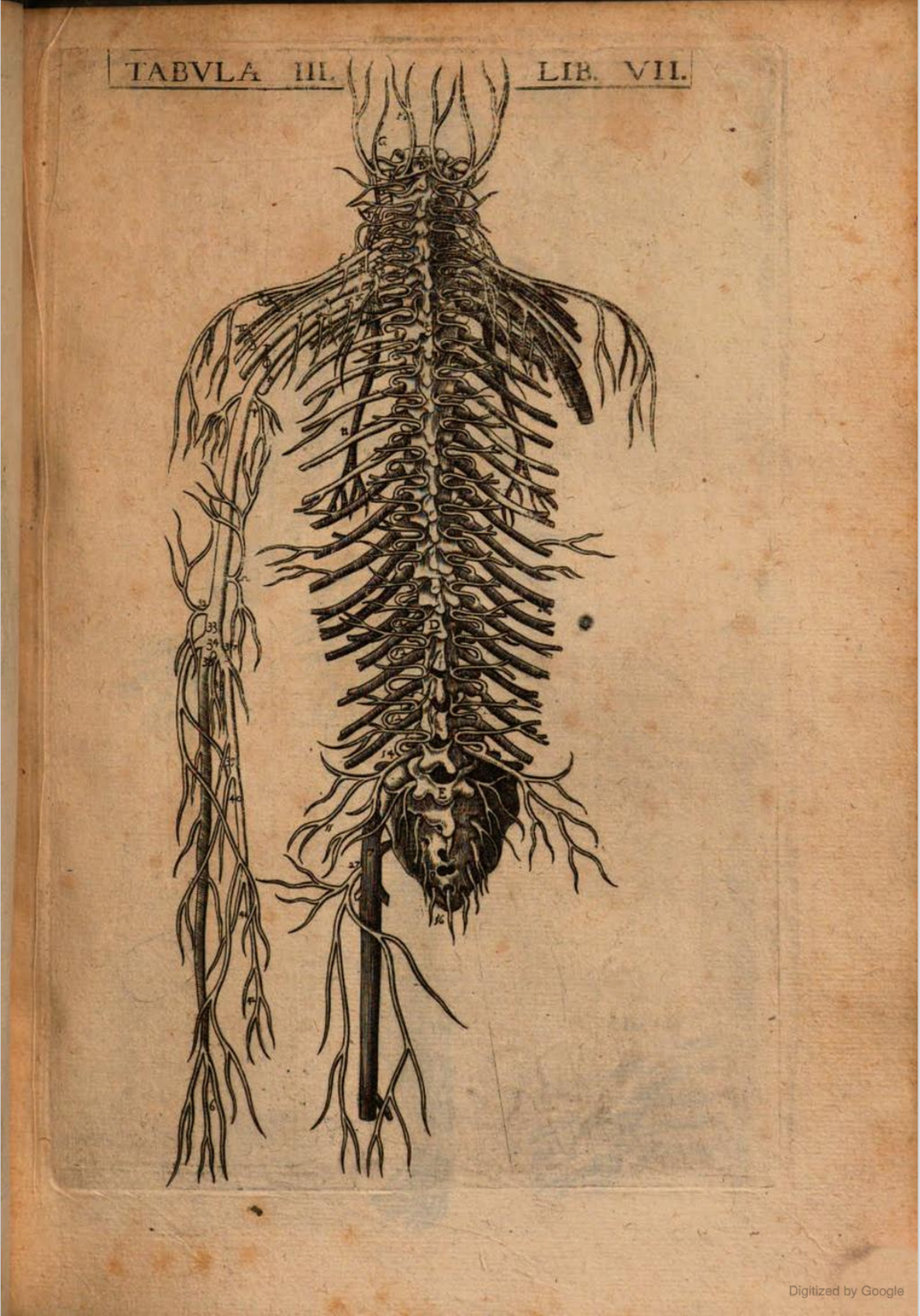

Tabula III., Libri VII. The left arm has been cut off and the leg shortened in Kaitai shinsho.

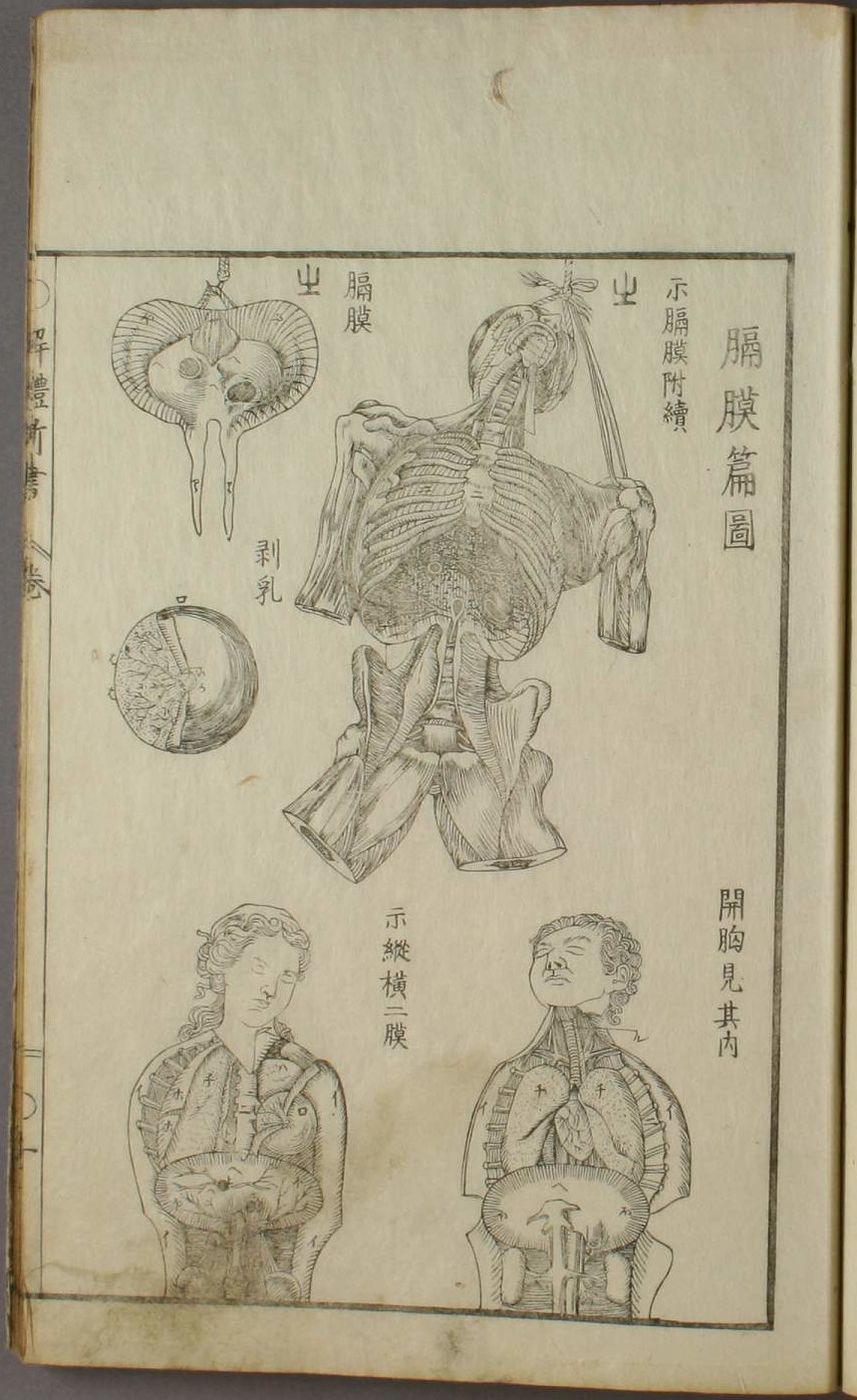

Page ten of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. Text reads, from left to right, "Showing the diapgrahm (membrane) continues to be attached," "diapgrahm (membrane)".

Tabula VII., Libri II. The legs, arms and background have been omitted in Kaitai shinsho.

Blankaart

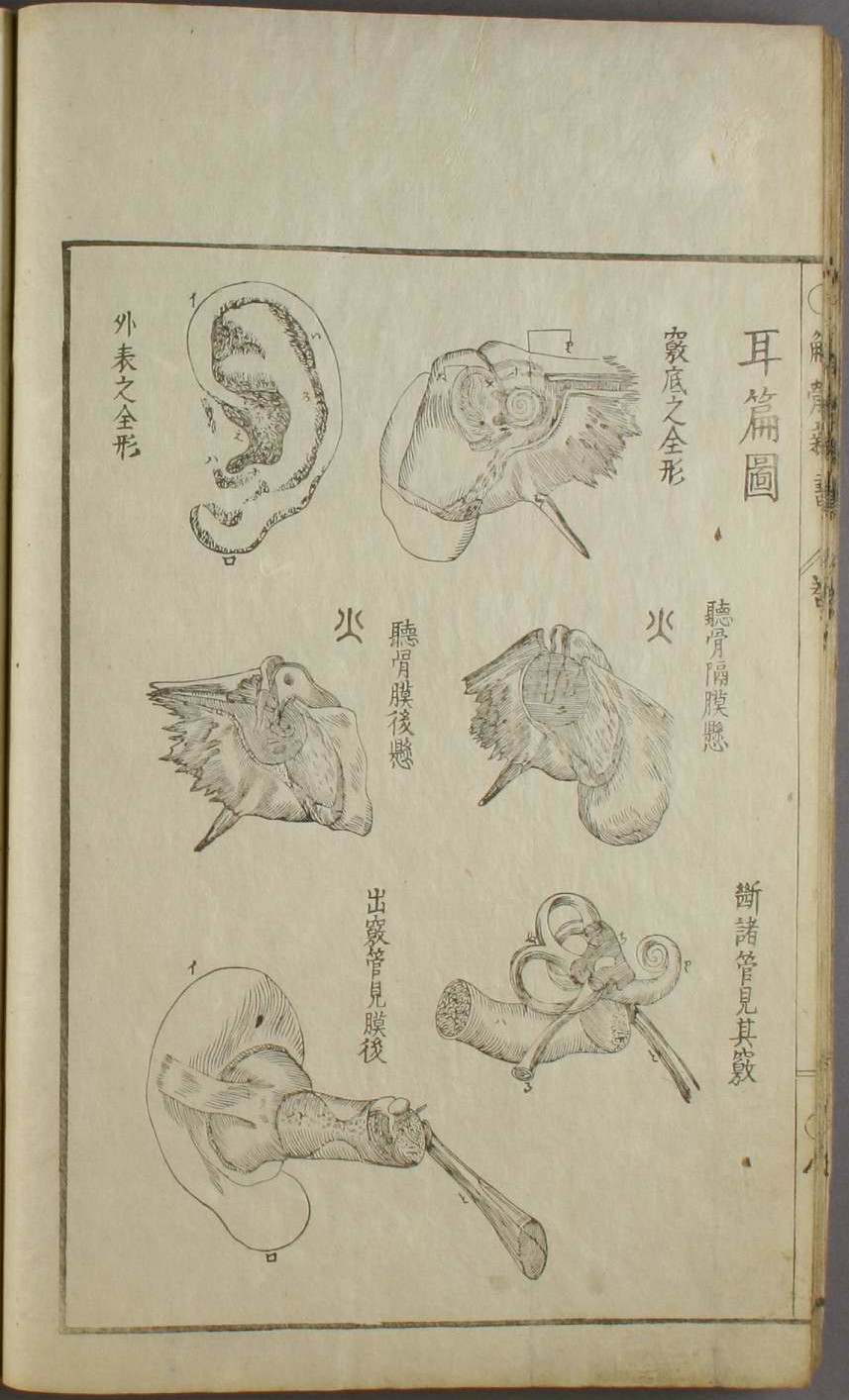

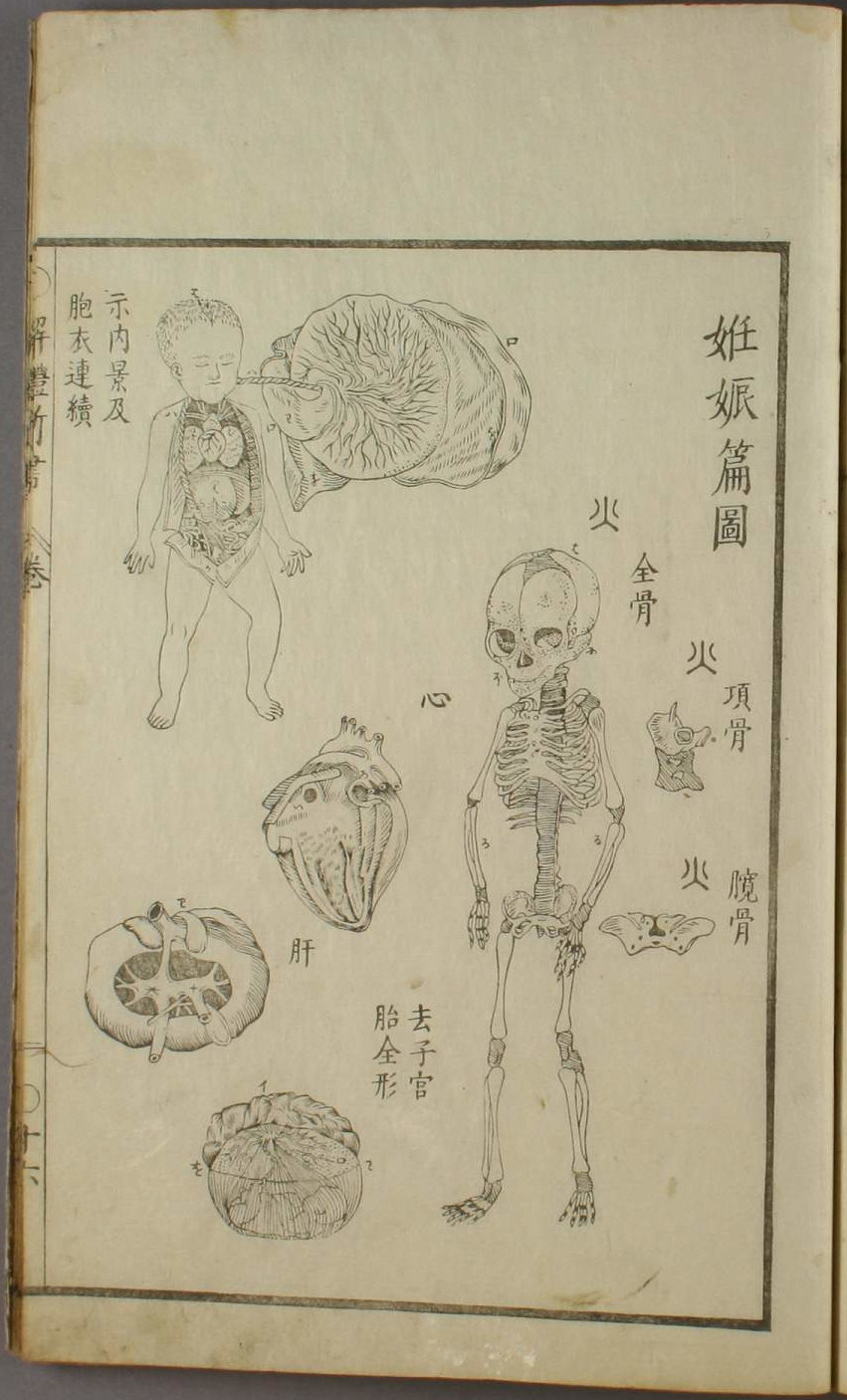

Page three of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. Images marked with the kanji 火 are taken from Blankaart’s work. The text reads, "ossicles, to be continued".

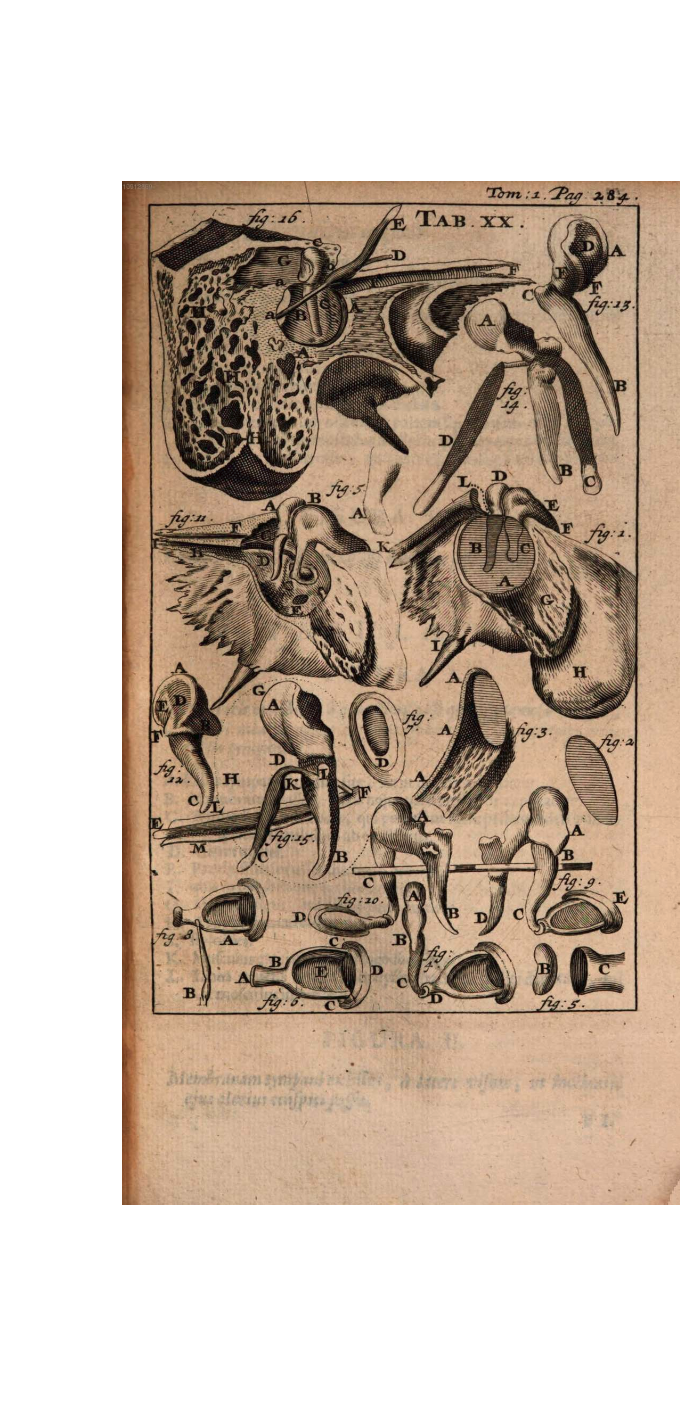

Page eight of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. The text reads, from left to right, "the ossicles is isolated, the membrane is in a suspended state," and "the ossicles and the membrane in a suspended state from the back".

Tabula 20. Fig.1, fig.11 and fig.20 are a match.

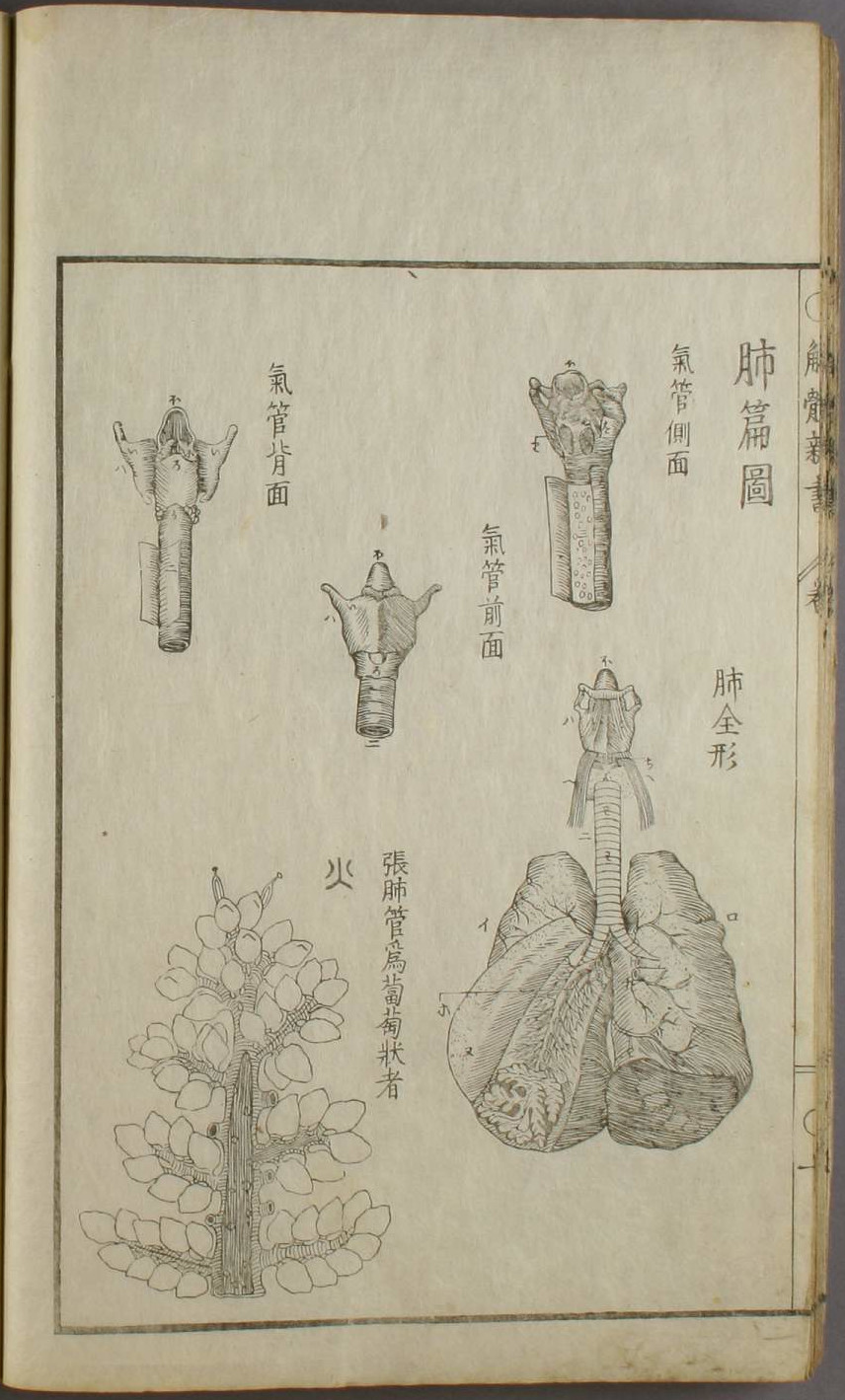

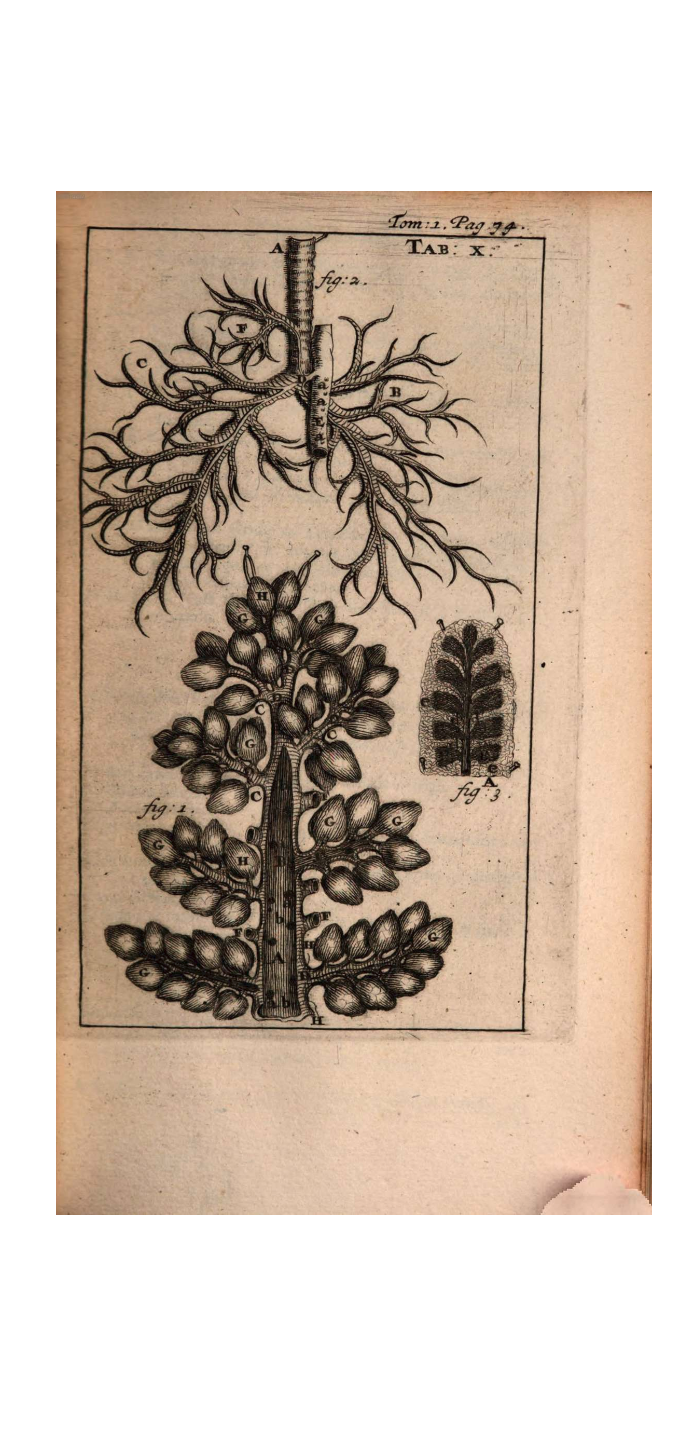

Page ten of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. The text reads, "A tube of the lung streched, with the abundant things shaped like radishes on a grapevine". This image comes from the original’s phrasing, which says “Lobuli secundarii Bronchiorum caudicibus tanquam uvae appensi,” that the lobes of the secondary branch hang like grapes.

Tabula 10. Fig.1 is a match.

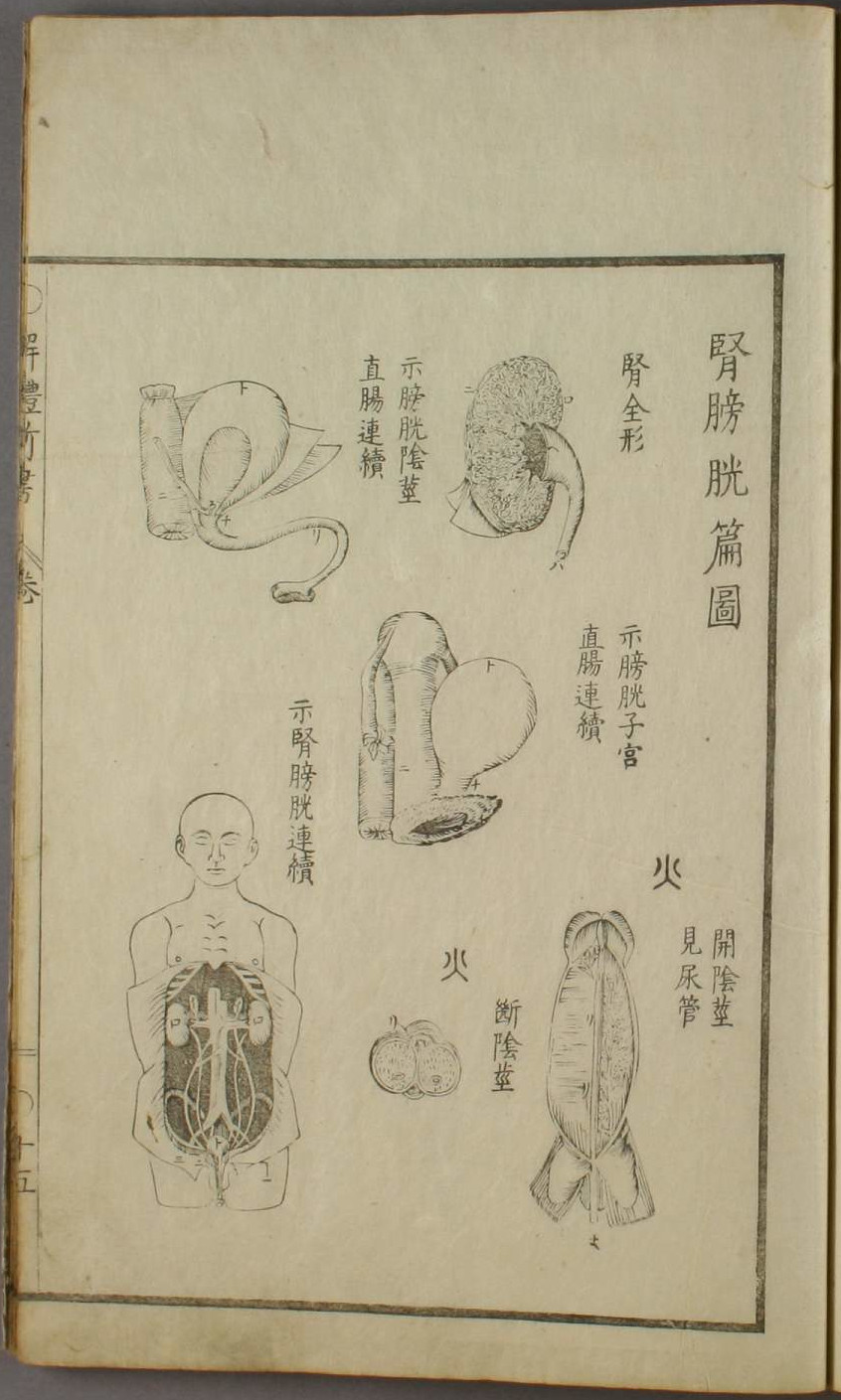

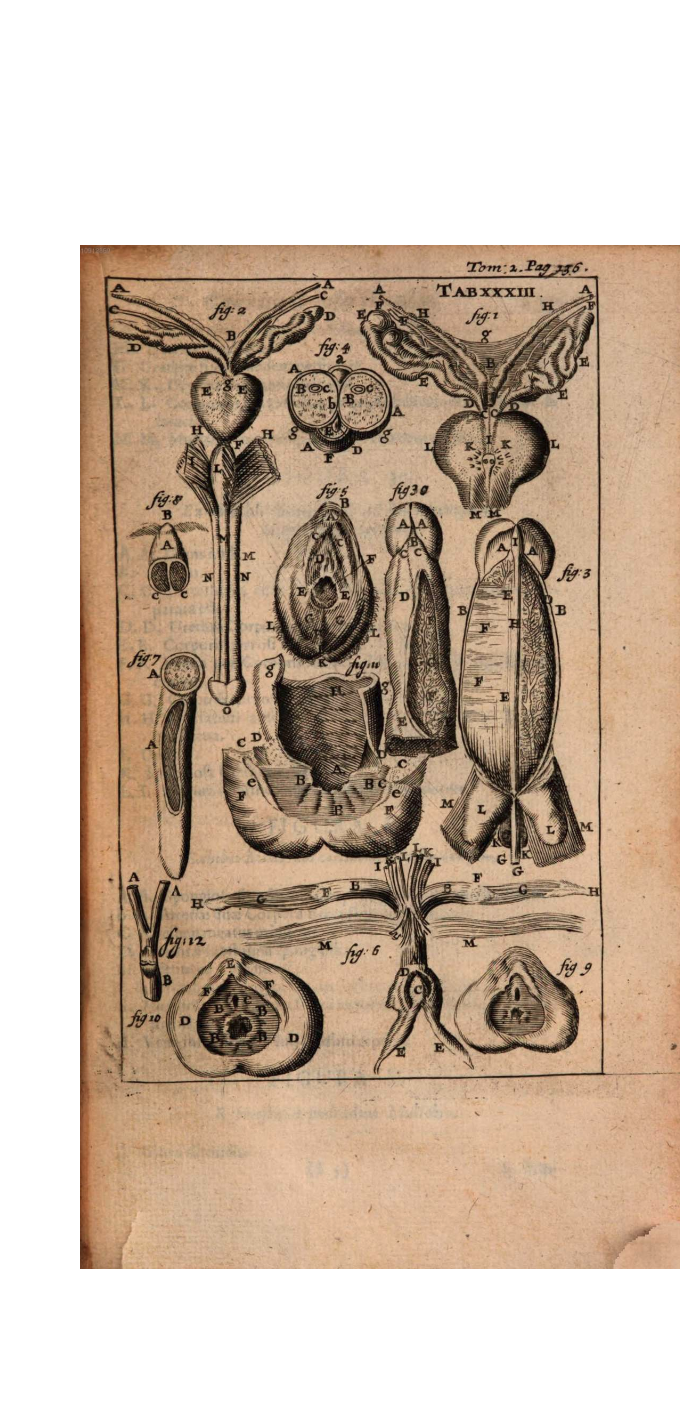

Page fifteen of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. The text reads, from left to right, "the opened penis, showing the urinary tract," and "severed penis".

Tabula 33. Fig.3 and fig.4 are a match.

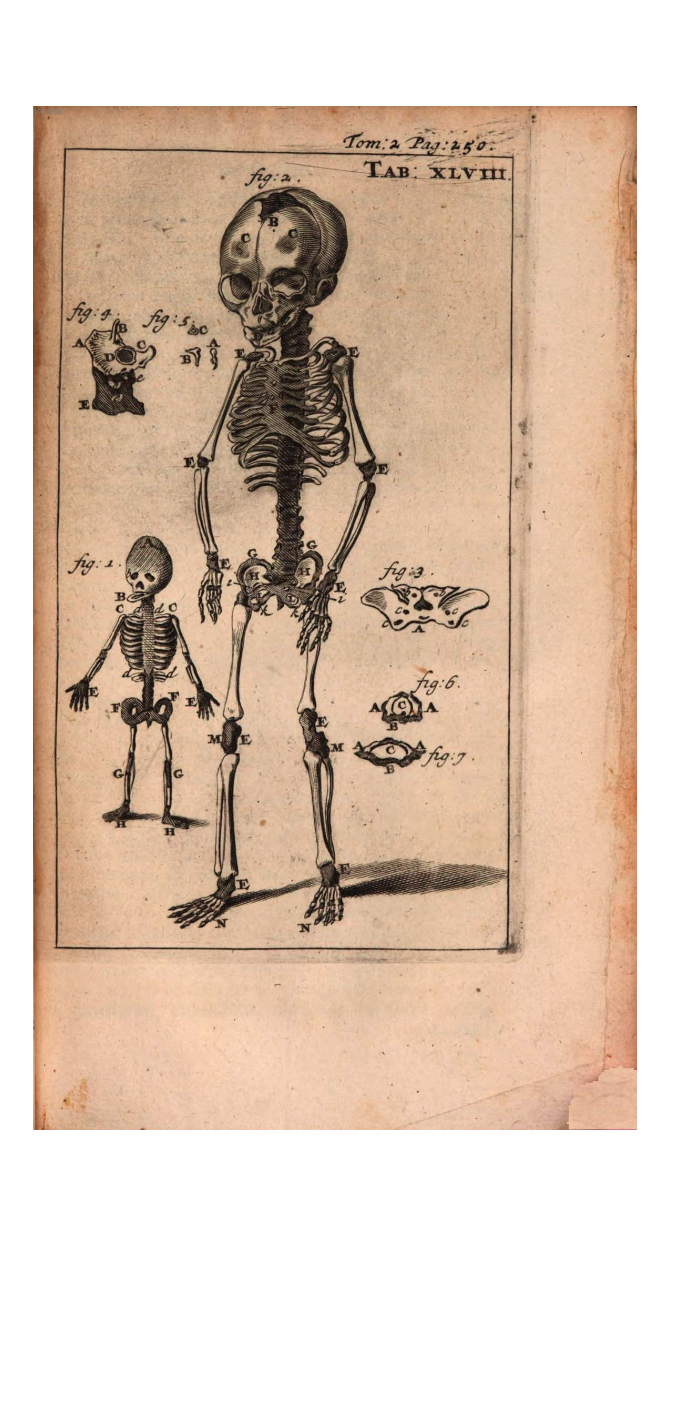

Page sixteen of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. The main text states these are illustrations about pregnancy. The text reads, from top to bottom, "all the bones [of the fetus]," "neck bone," and "ilium".

Tabula 48. Fig.2 fig.3 and fig.4 are a match.

Bidloo

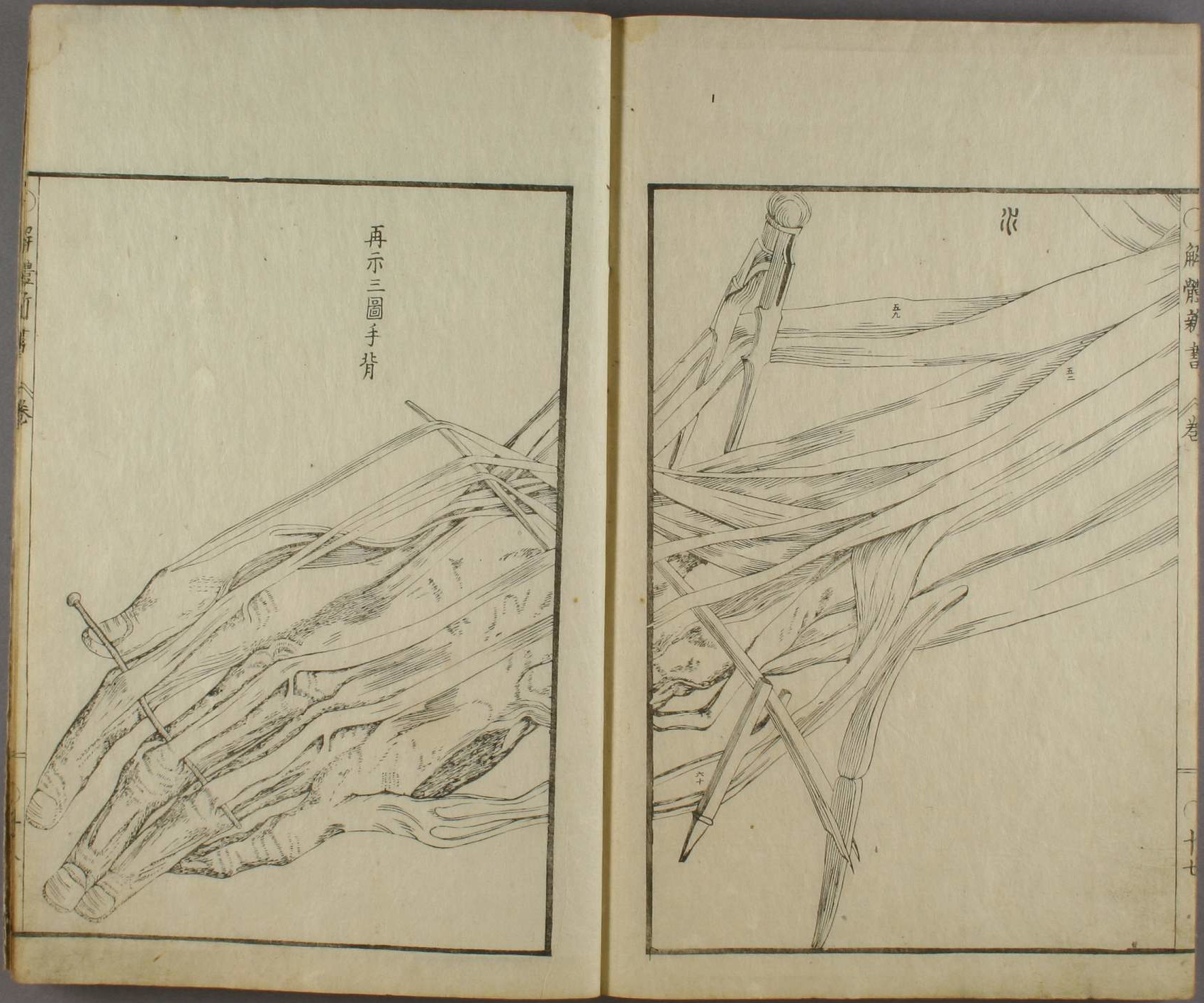

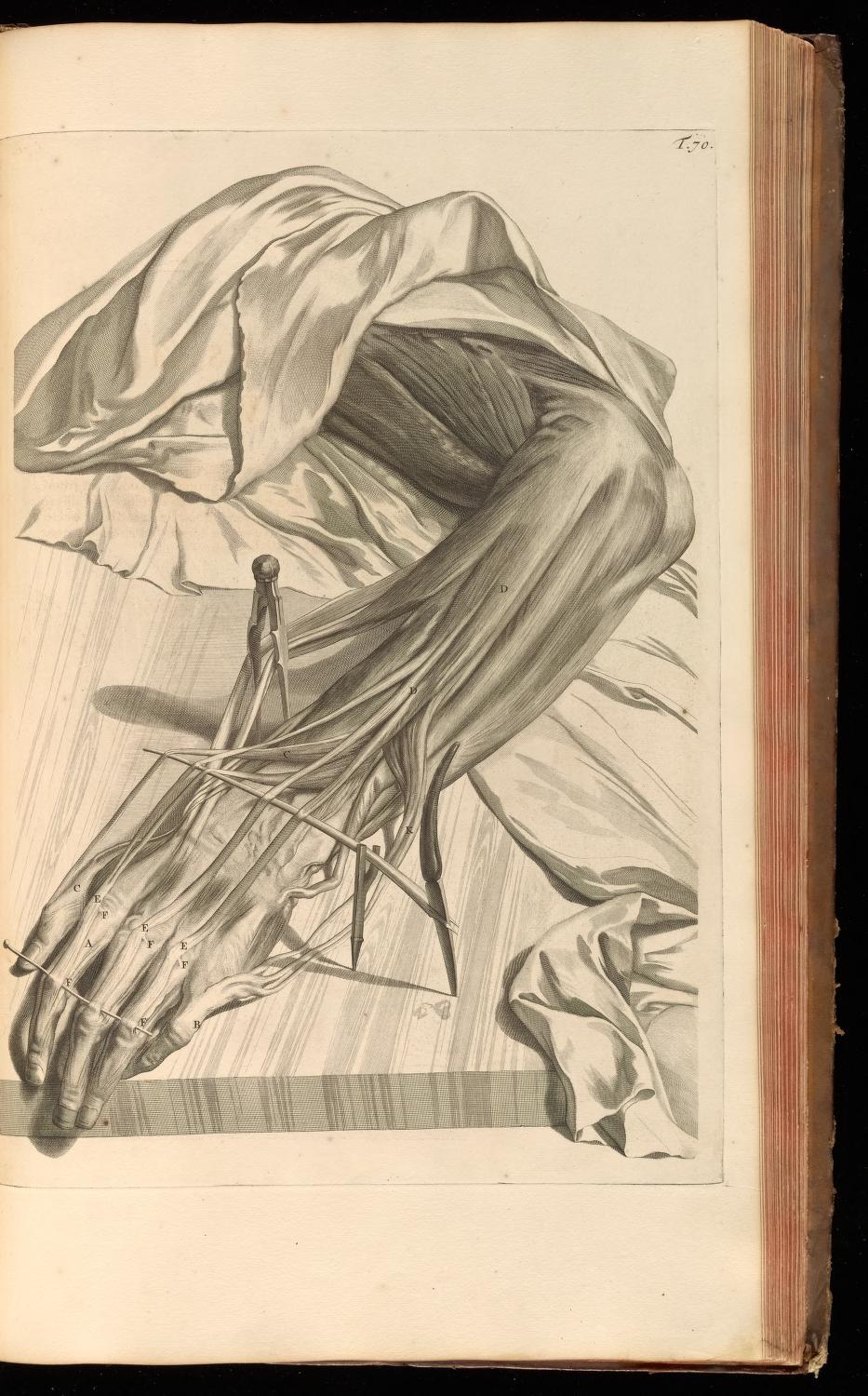

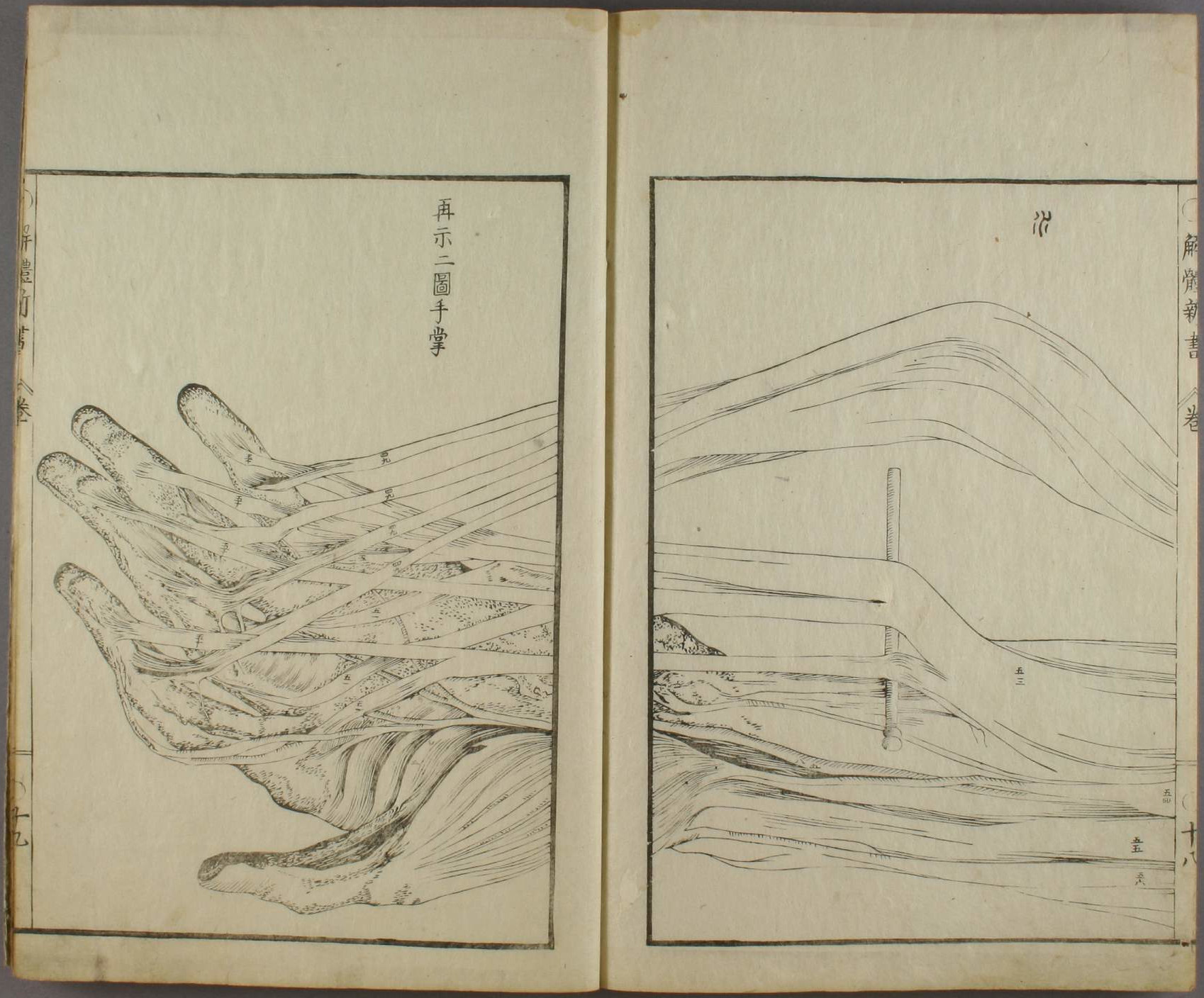

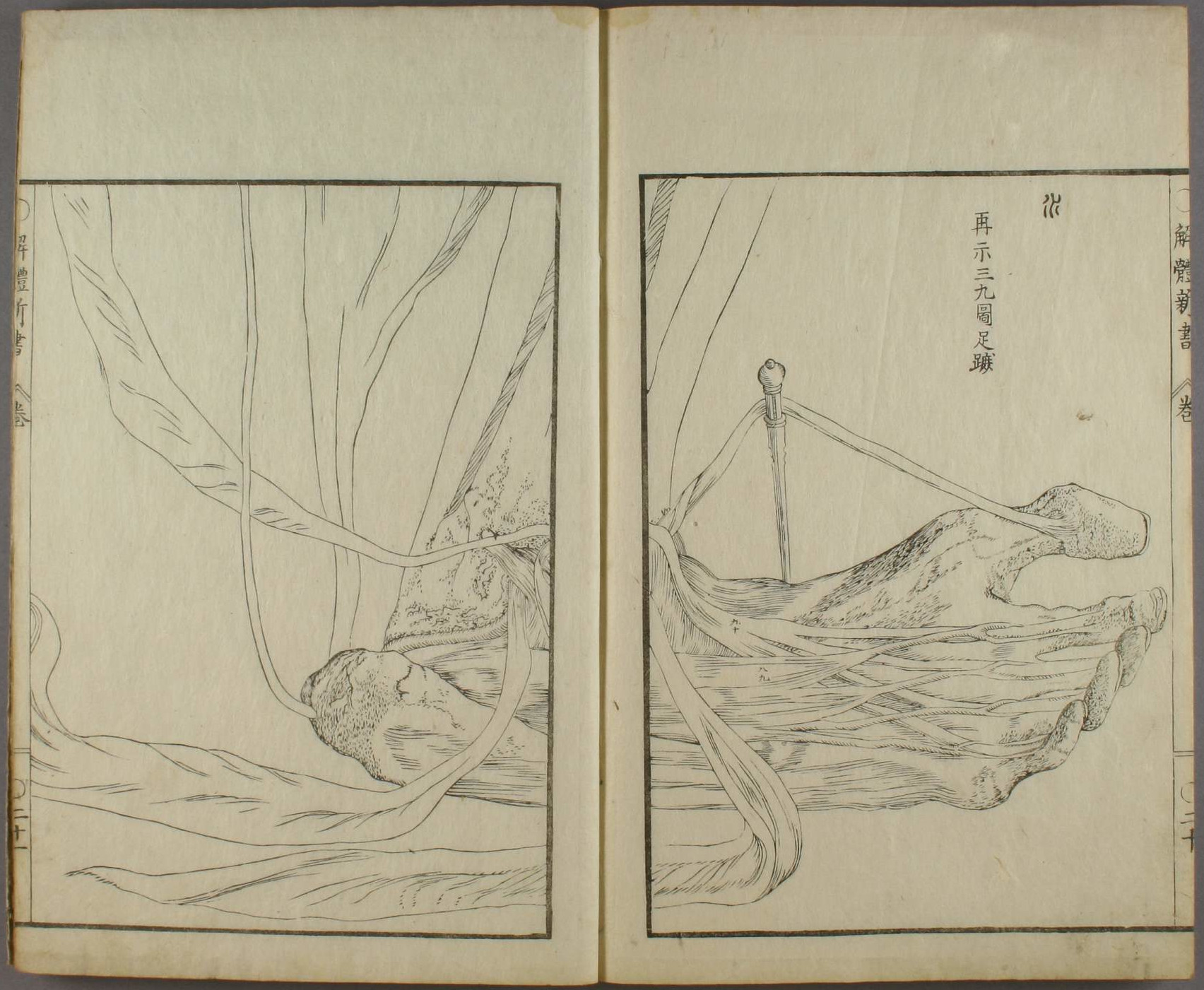

Pages seventeen and eighteen of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. Images marked with the kanji 水 are taken from Bidloo’s work. The text reads, "Showing again. Third figure. Back of the hand.".

Table 70. Slightly rotated in Kaitai shinsho, closeup.

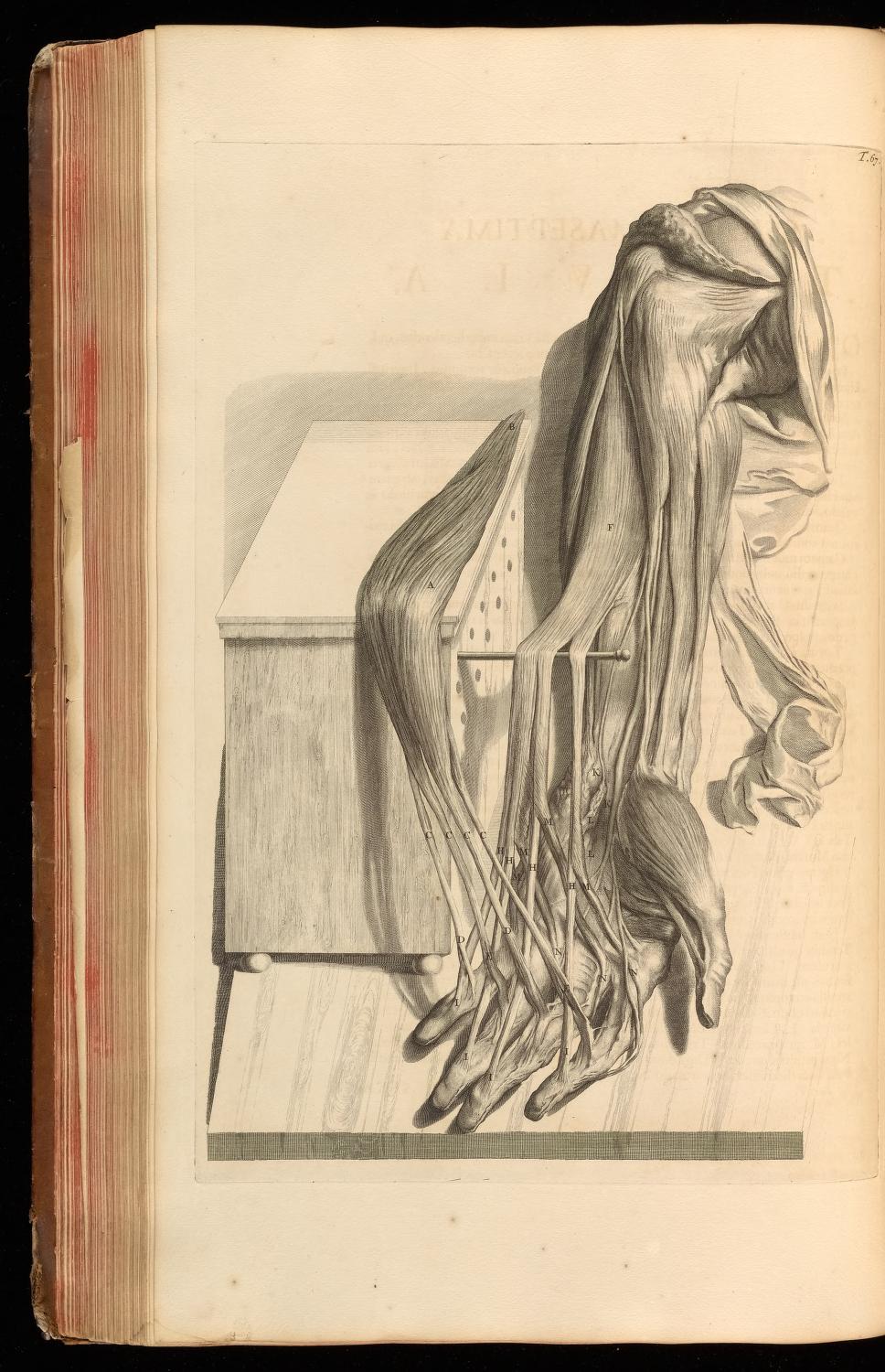

Pages eighteen and nineteen of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. The text reads, "Showing again. Second figure. Palm of the hand.".

Table 67. Rotated to the right in Kaitai shinsho, closeup.

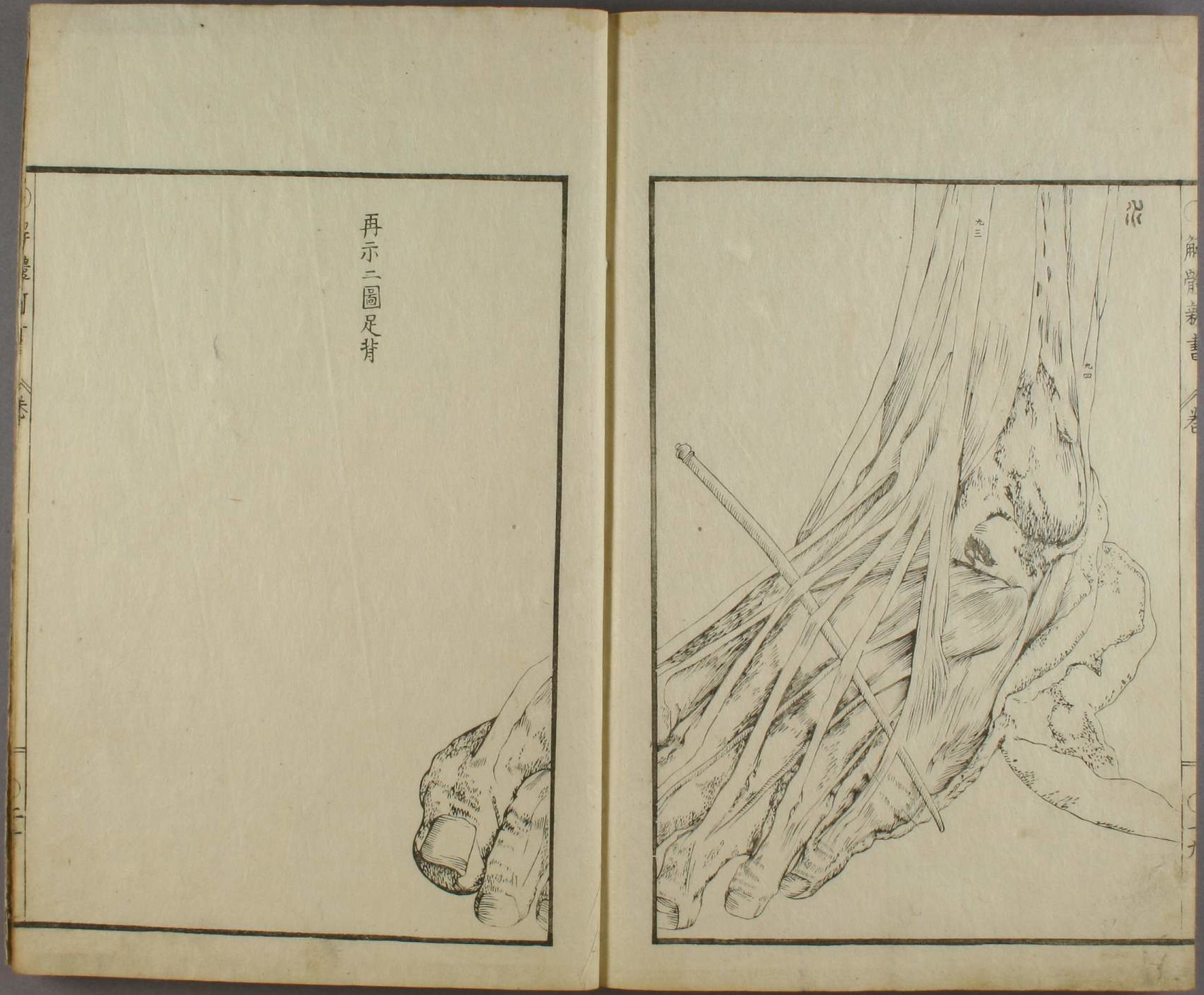

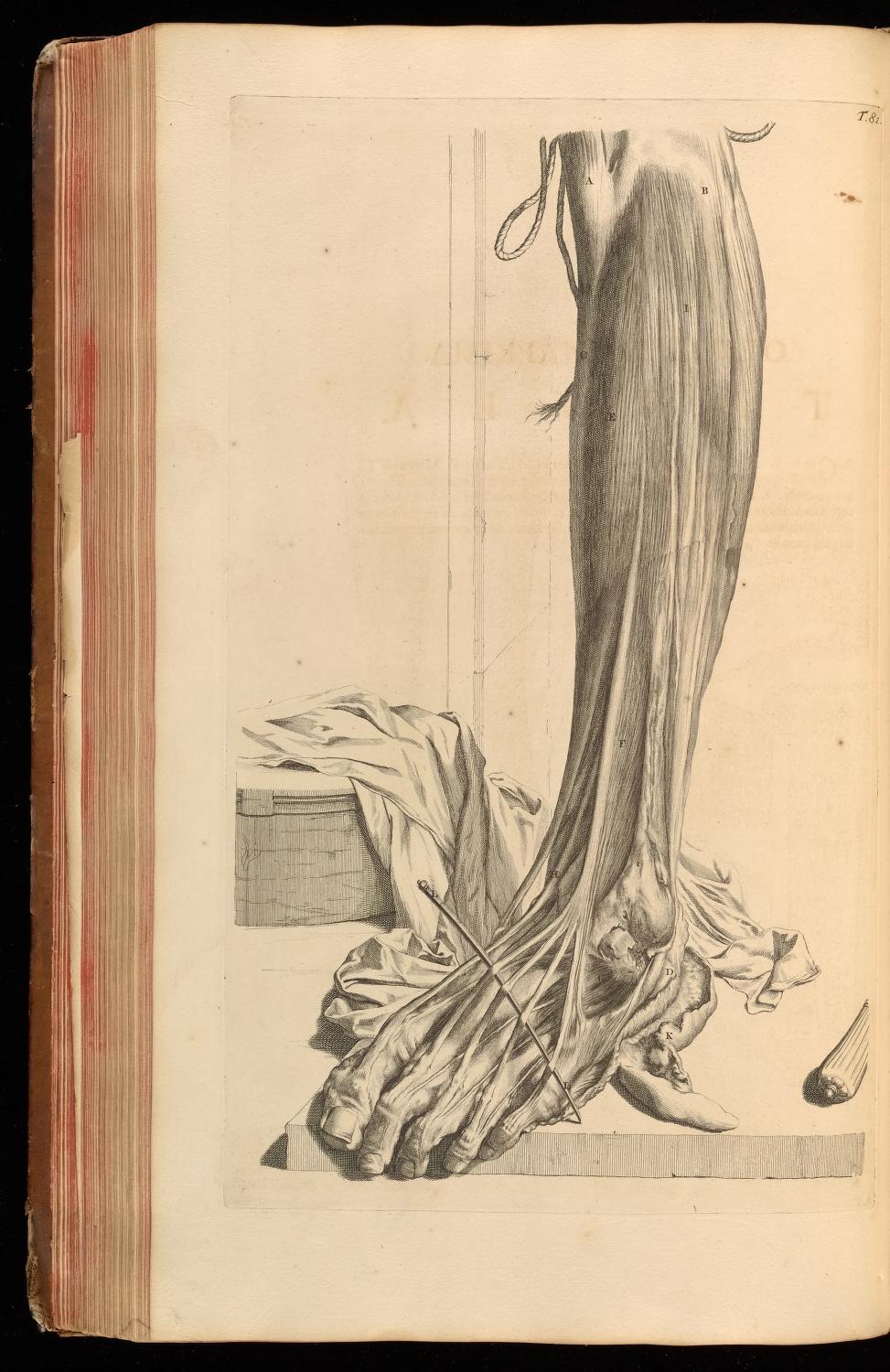

Pages nineteen and twenty of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. The text reads, "Showing again. Second figure. Back of the foot.".

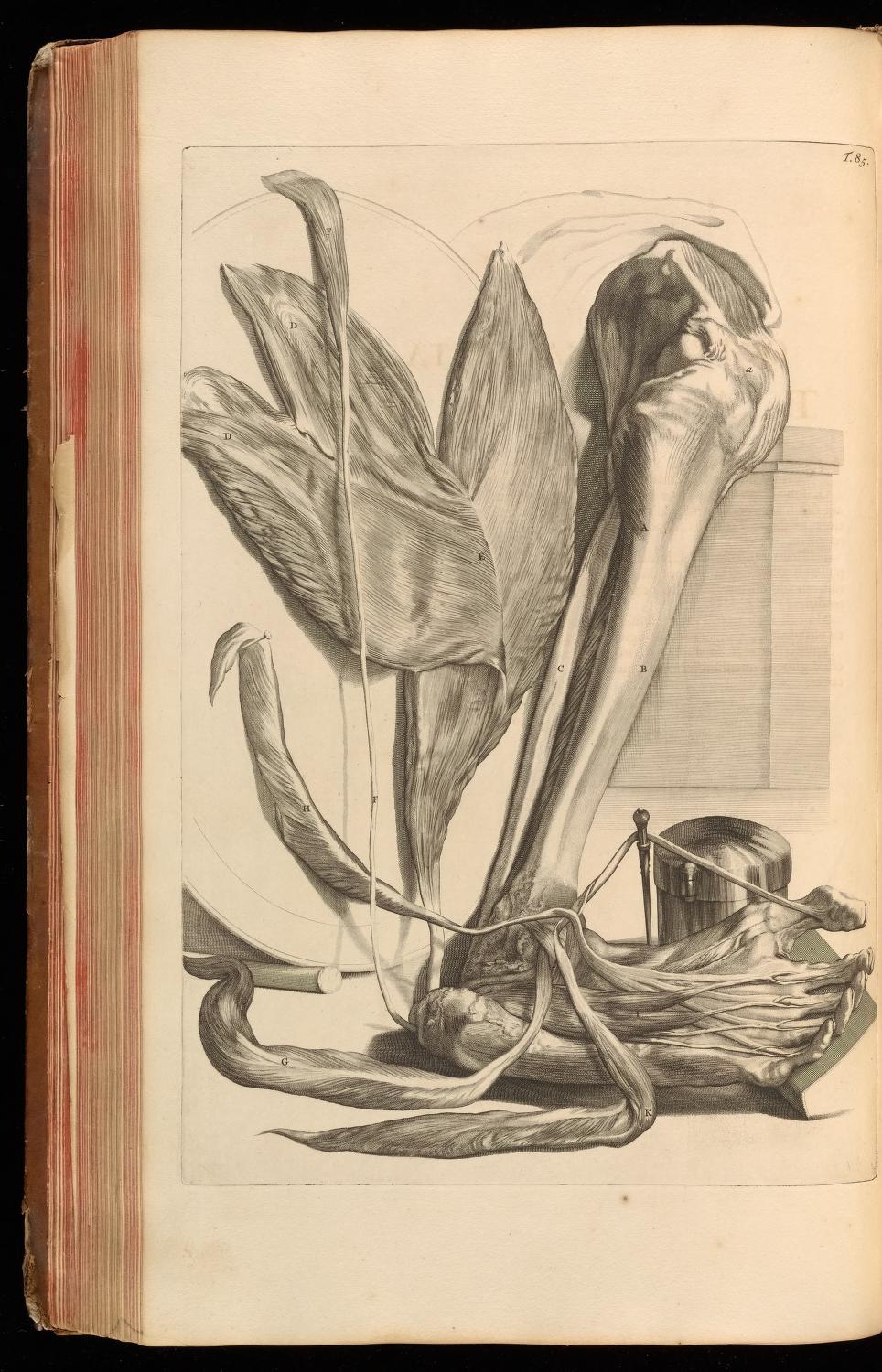

Table 81. Closeup in Kaitai shinsho.

Pages twenty and twentyone of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. The text reads, "Showing again. Thirty-ninth figure. Sole of the foot.".

Table 85. Closeup in Kaitai shinsho.

Bartholin

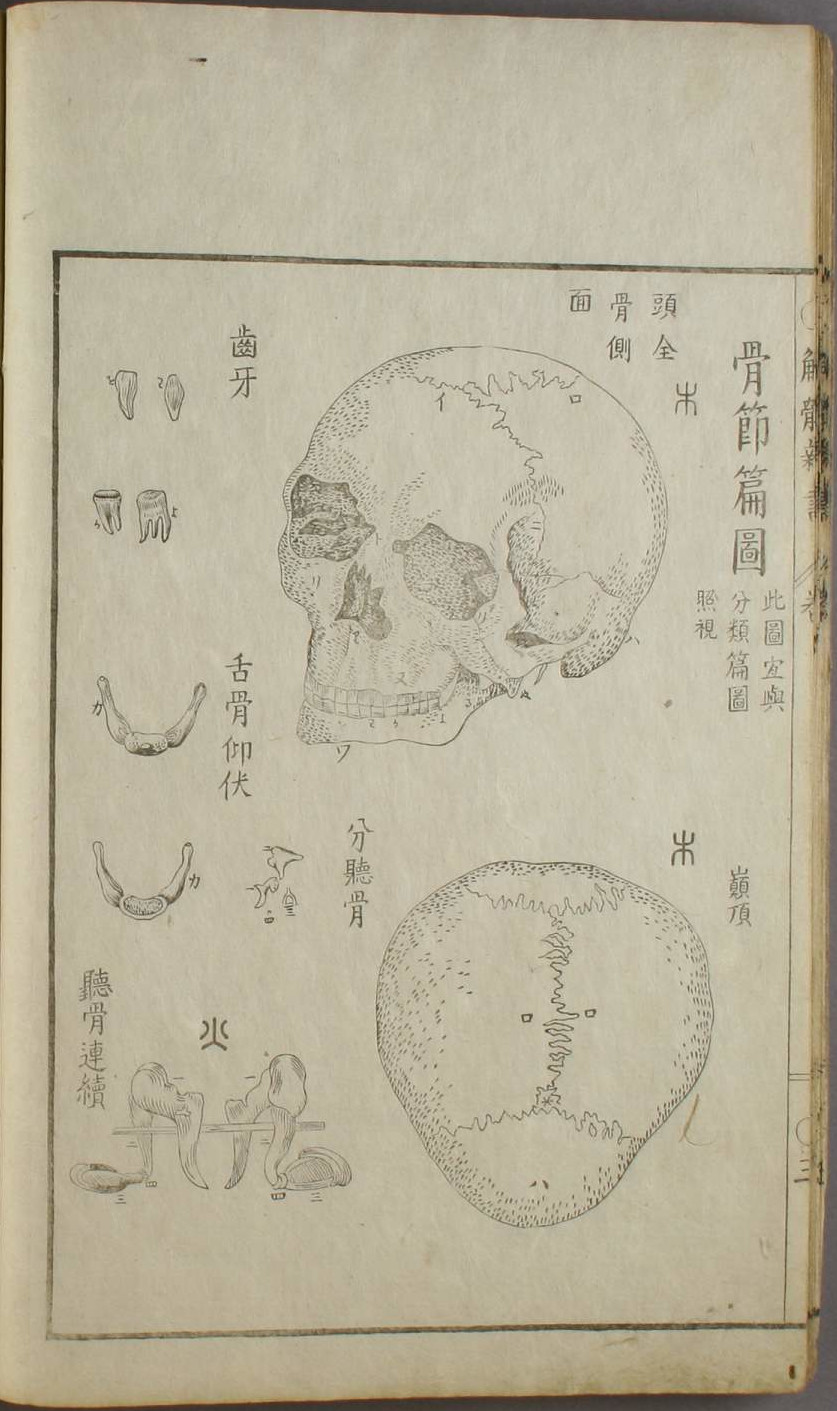

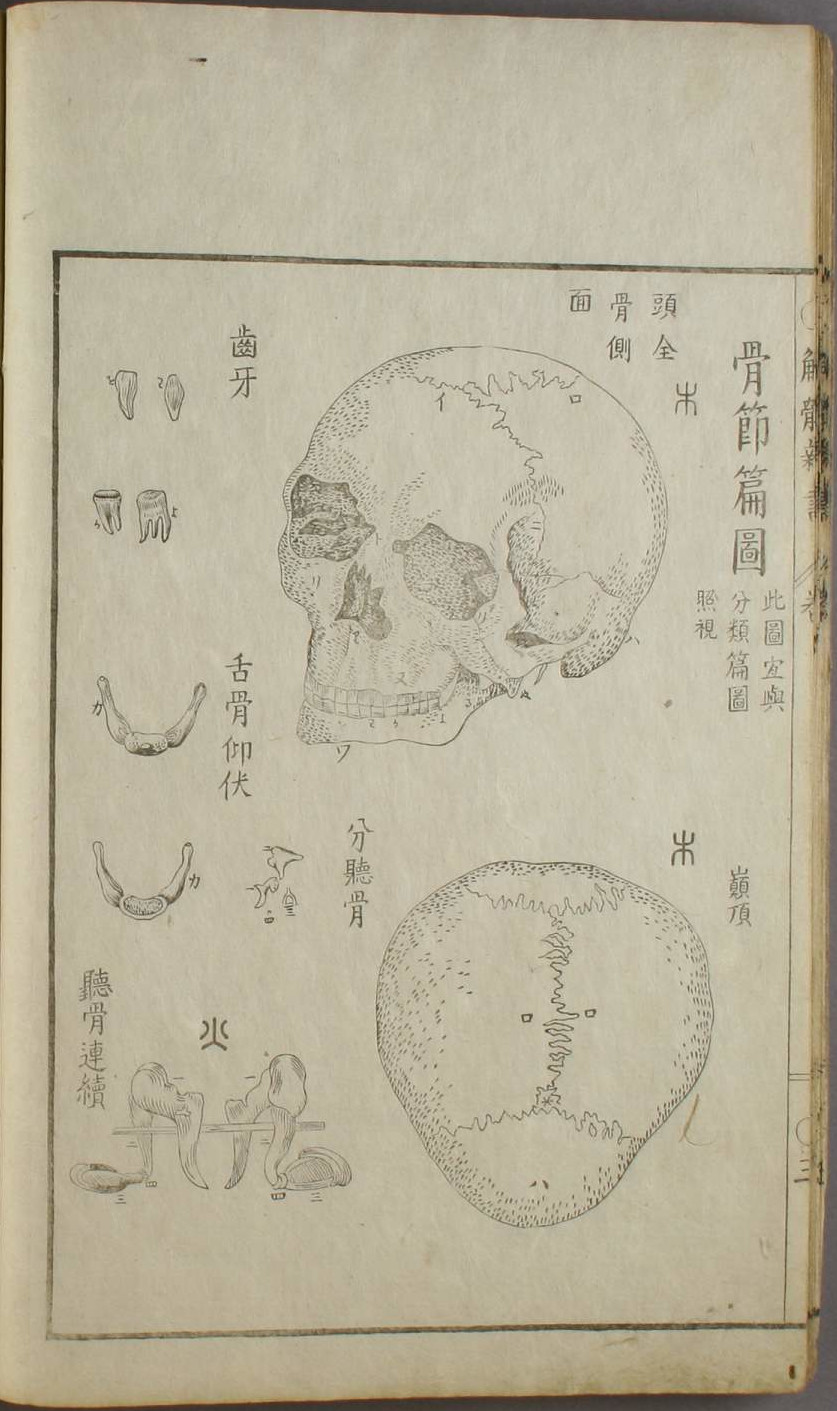

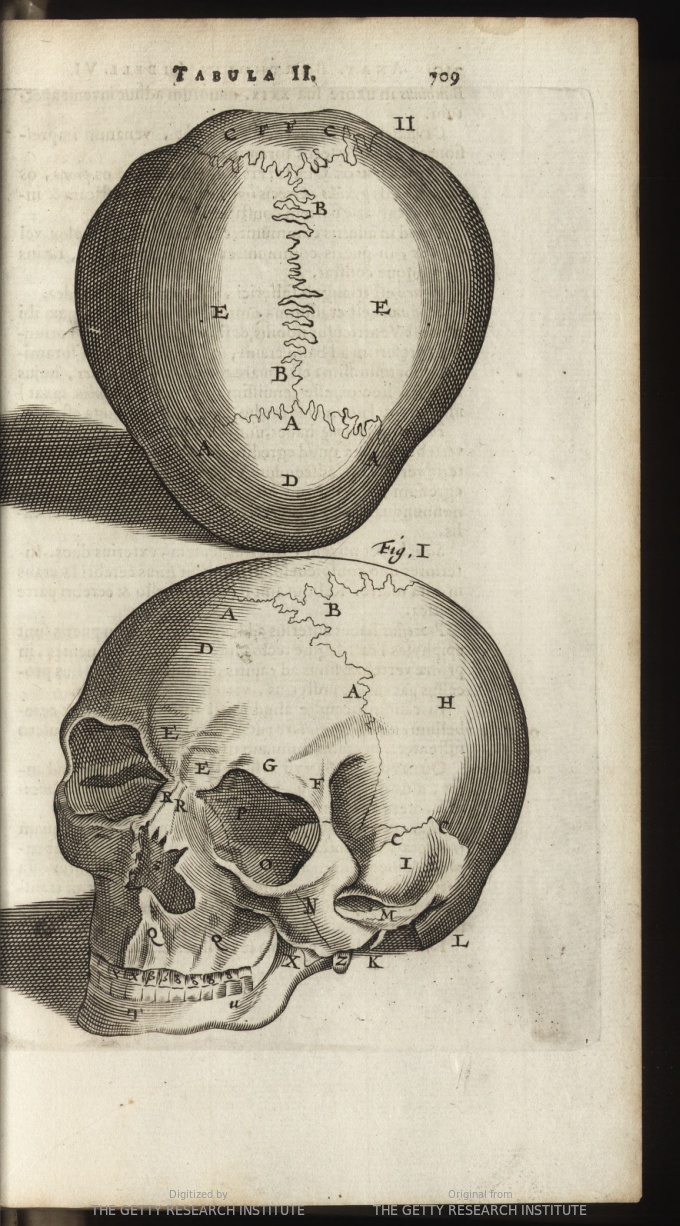

Page three of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. Images marked with the kanji 木 are taken from Bartholin’s work. The text reads, from top to bottom, "all the bones in the head, side view," and "the top of the head".

Book Four. Table 2. Figure I and II are a match.

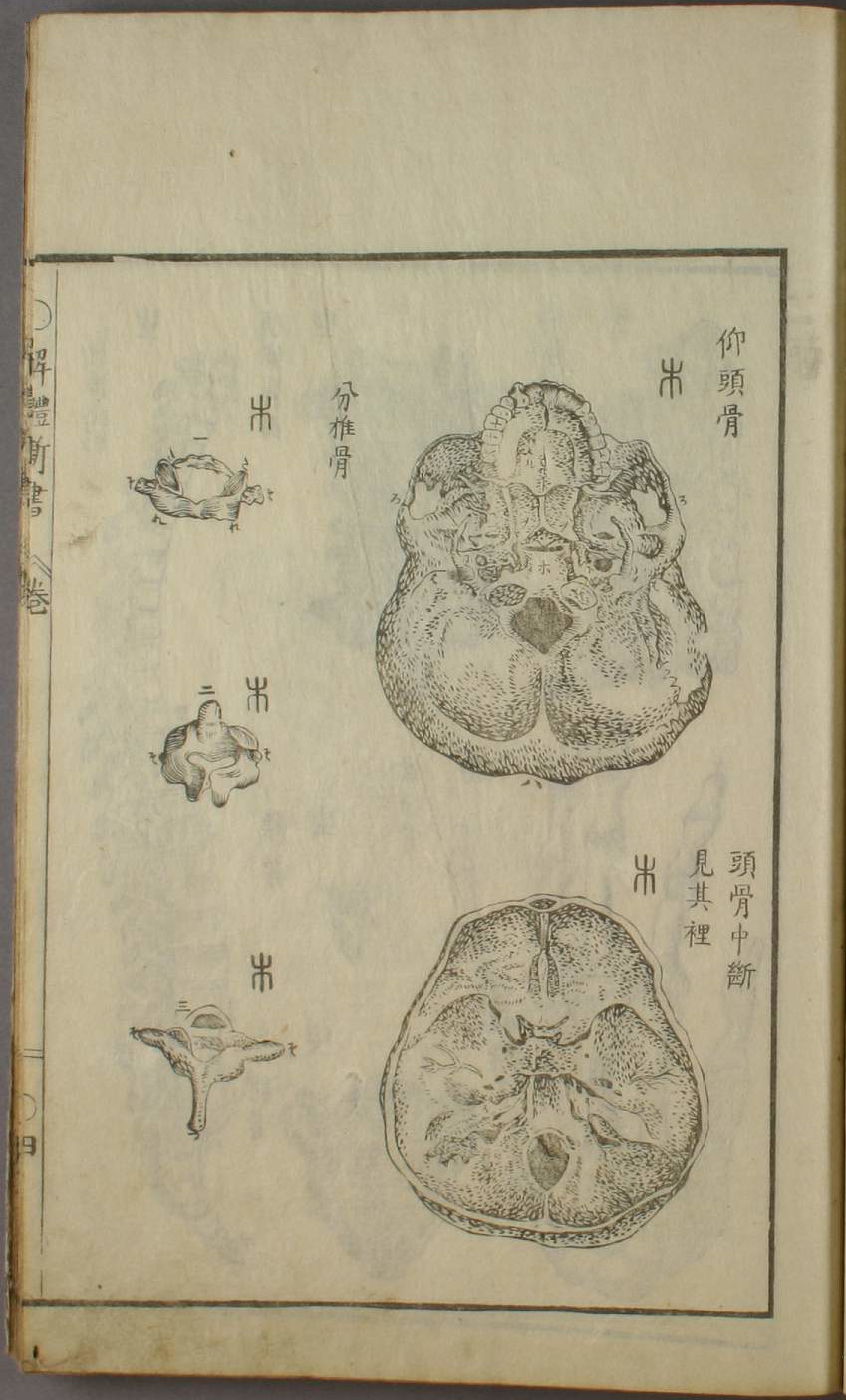

Page four of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. The text reads, from left to right, top to bottom, "looking into the skull," "the skull cut in half, looking inside," "bone from part of the spine".

Book Four. Table 6. Figure I and II are a match.

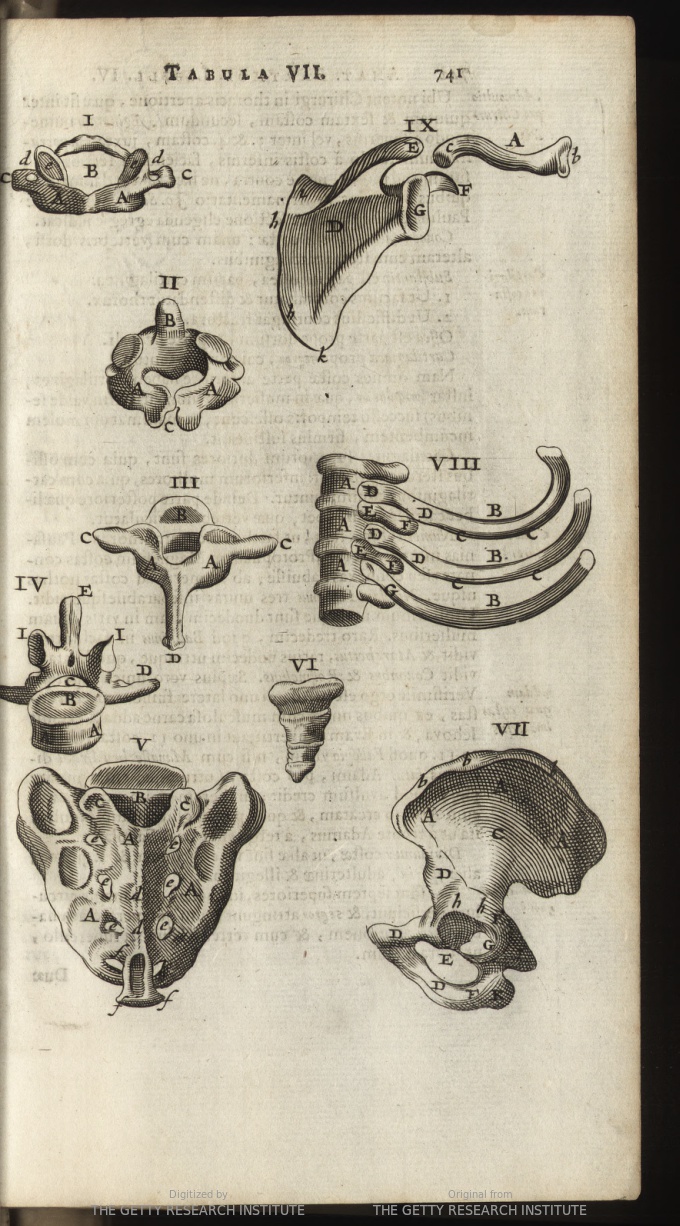

Book Four. Table 7. Figure I, II and III are a match. Figures V and VI also seem to match those attributed to Valverde from page four. Figure IX is reproduced on page five.

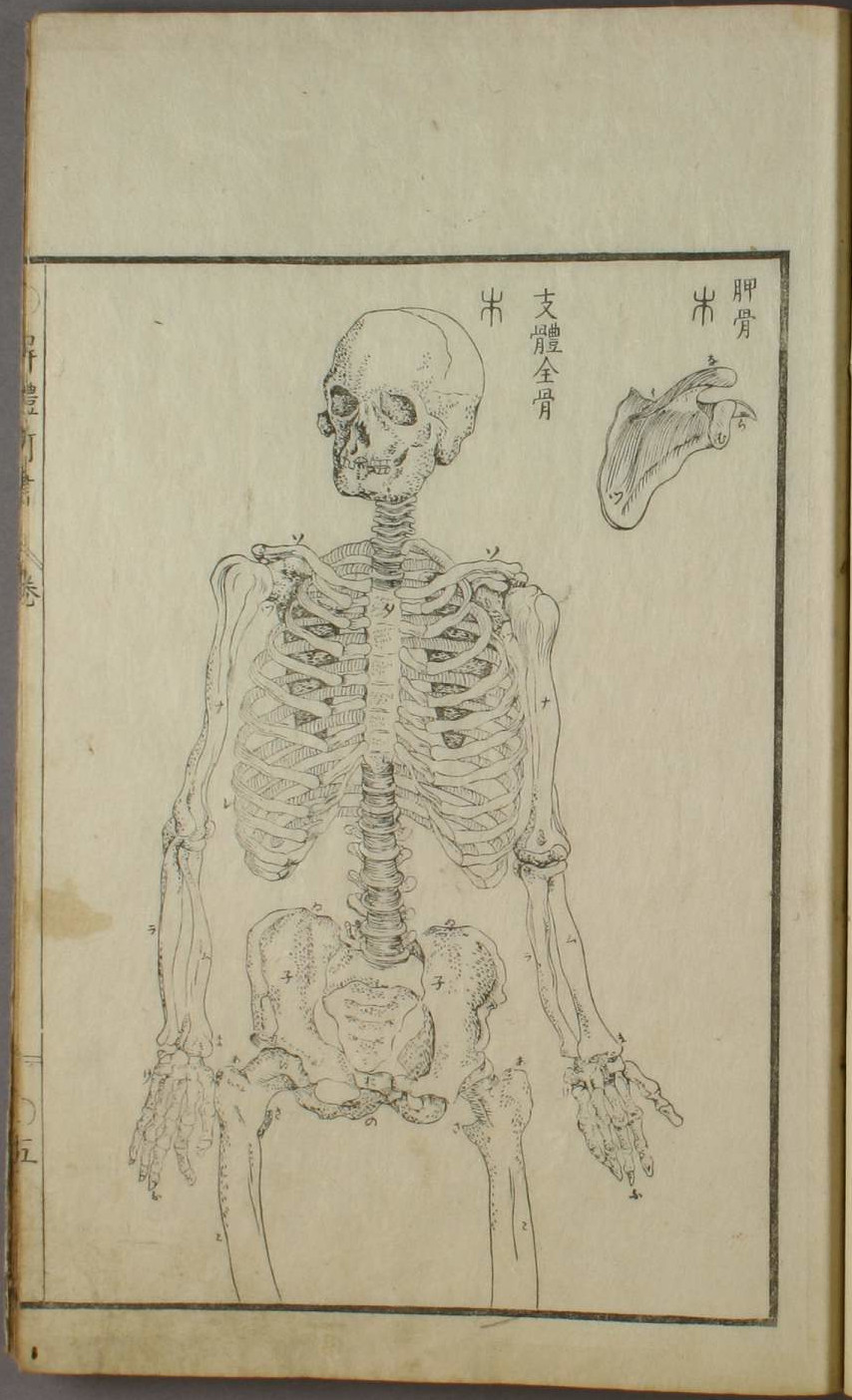

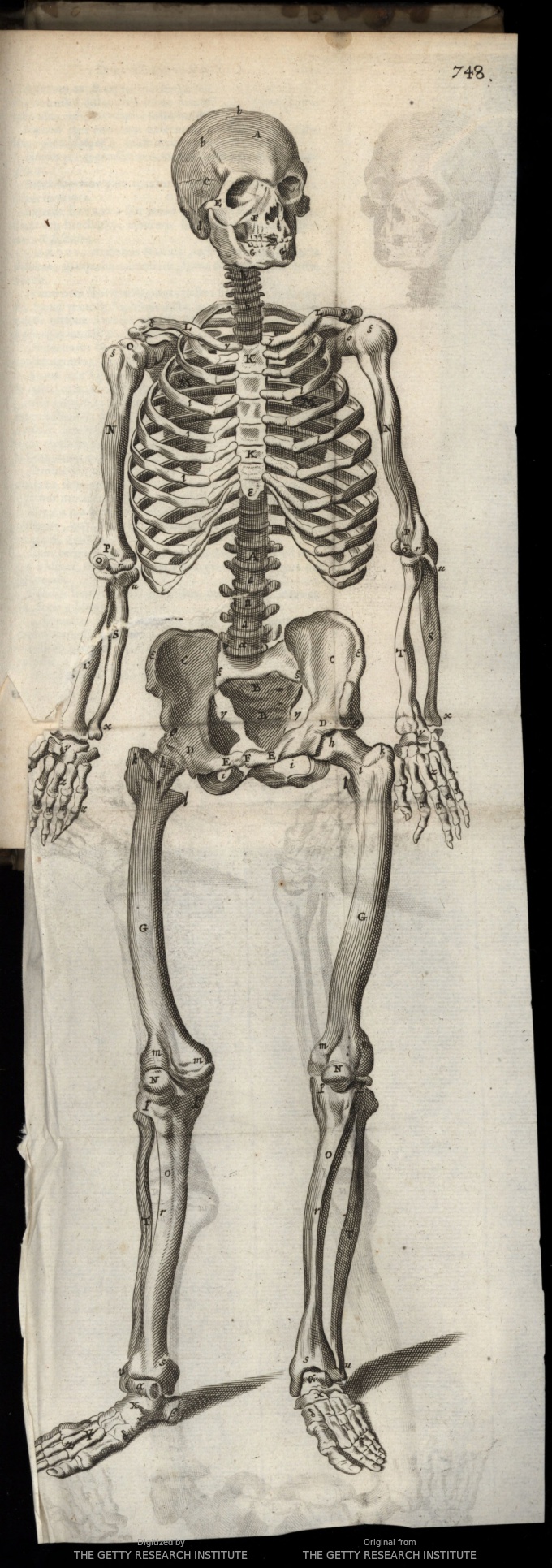

Page five of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. The text reads, from left to right, "shoulder blade bone," and "all the bones in the body, held up". The skeleton’s feet are found on the other side of page five.

Book Four. Skeleton foldout. The copy in Kaitai shinsho has been mirrored and split across two pages.

Paré

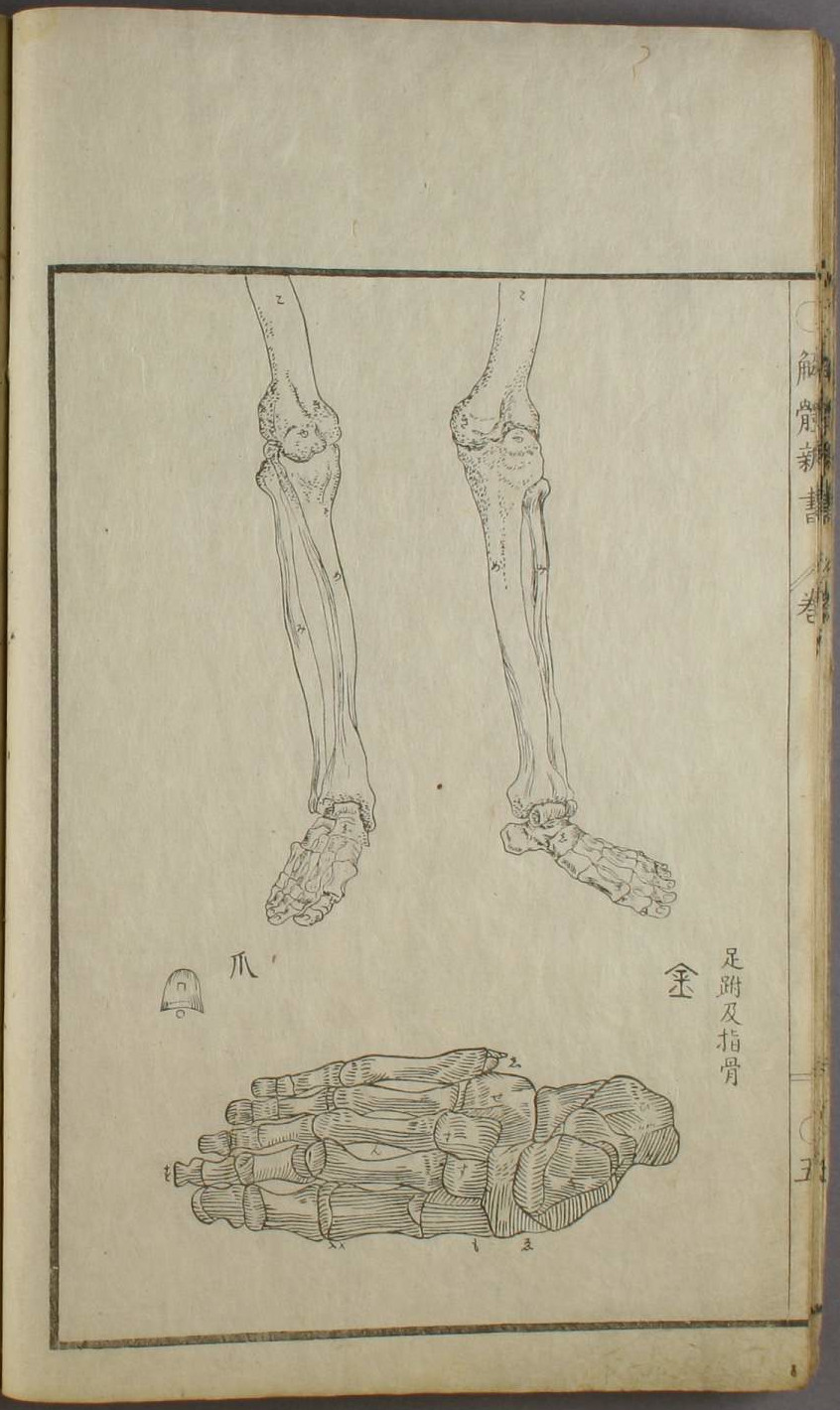

Page five of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. Images marked with the kanji 金 are taken from Valverde’s work. The text reads, "bones of the ankle and toes".

Page four of Kaitai shinsho’s illustration volume. Images marked with the kanji 山 are taken from Valverde’s work. The text reads, from left to right, "the whole form of the spine," "the nape of the neck from the rear,"the nape of the neck in profile," "coccyx*," "sacrum*". The hand is taken from Paré, the text reads, "bones of the palm and hand".

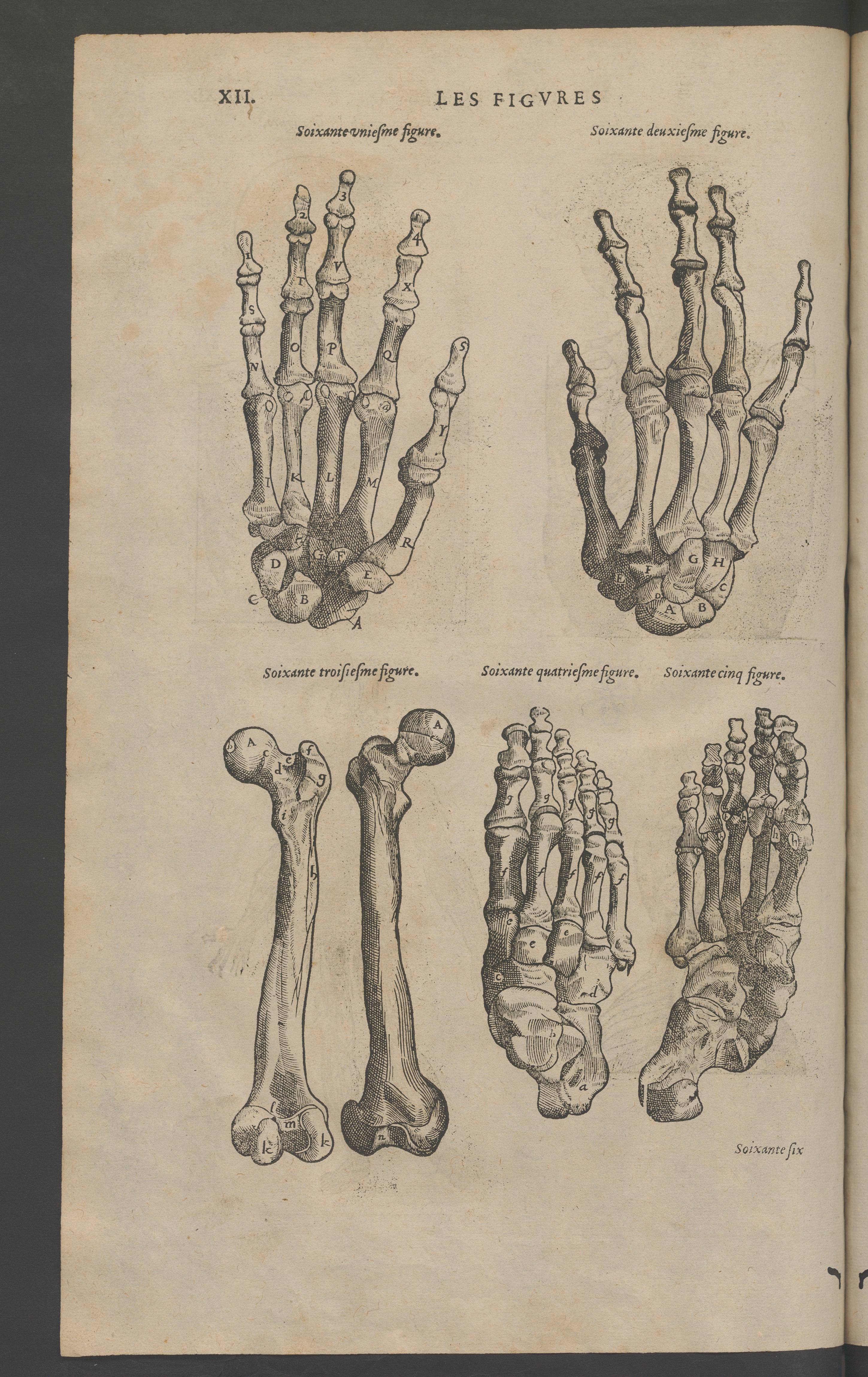

Figure sixty-two (hand palm down) and sixty-four (foot sole down) are a match.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

| Bartholin, Thomas, Johannes Walaeus, and Caspar Bartholin. Anatome ex omnium veterum recentiorumque observationibus inprimis institutionibus b.m. Anatome ex omnium veterum recentiorumque observationibus inprimis institutionibus b.m. parentis Caspari Bartholini. Lugduni Bata- vorum: Apud Jacobum Hackium, 1686. As digitized by the Getty Research Institute and hosted on archive.org. https://archive.org/details/gri_33125010543912/page/n5 Date accessed: 2019.10.29. |

| Bidloo, Govard. Anatomia humani corporis, centum & quinque tabulis per artificiosiss. Amstelodami: Sumptibus viduae Joannis à Someren, haere- dum Joannis à Dyk, Henrici & viduae Theodori Boom, 1685. As digitized by the Getty Research Institute and hosted on archive.org. https://archive.org/details/gri_33125008642049/page/n6 Date accessed: 2019.10.29. |

| Blankaart, Steven. Anatomia reformata. Lugdunum Batavorum: Apud Cornelium Boutesteyn, Jordanum Luchtmans, 1687. As digitized by the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. https://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs1/object/display/bsb10912869_00005.html Date accessed: 2019.02.18. |

| Kulmus, Johann Adam. Anatomische Tabellen Nebst dazu gehörigen Anmerckungen und Kupffern, Daraus des gantzen Menschlichen Körpers Beschaffenheit und Nutzen deutlich zu ersehen, Welche Den Anfängern der Anatomie zu bequemer Anleitung verfasset hat. Vierte Aufflage, Viel vermehrt, und mit neuen Kupffern versehen. Augspurg: Lotter, 1740. As digitized by the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0007/bsb00078350/images/ Date accessed: 2019.02.18. |

| Paré, Ambroise. Les oeuvres d’Ambroise Paré. Paris: Gabriel Buon, 1579. As digitized by the BPU Neuchâtel and hosted on e-rara.ch. https://doi.org/10.3931/e-rara-7520 Date accessed: 2019.10.29. |

| Sugita, Genpaku et al. Kaitai shinsho. Suharaya Ichibe shi, 1774. As digitized by the Wasdeda University Library. http://www.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kotenseki/html/ya03/ya03_01060/index.html Date accessed: 2019.02.18. |

| Valverde, Juan. Vivae imagines partium corporis humani aereis formis expressae. Latin. Antverpiae: Christophori Plantini, 1572. As digitized by Google. https://books.google.de/books?id=uUlcAAAAcAAJ&dq=Vivae+imagines+partium+corporis+humani+aereis+formis+expressae&source=gbs_navlinks_s Date accessed: 2019.02.18. |

Secondary sources

| Beerens, Anna. Friends, Acquaintances, Pupils and Patrons: Japanese Intellectual Life in the Late Eighteenth Century: a Prosopographical Approach. Amsterdam University Press, 2006. isbn: 9087280017. |

| Espesset, Grégoire and Gabor Lukacs. “Review of Kaitai Shinsho: The Single Most Famous Japanese Book of Medicine & Geka Sōden: An Early Very Important Manuscript on Surgery, by Gabor Lukacs”. In: East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine 40 (2014), pp. 113–128. issn: 1562-918X. |

| Goodman, Grant Kohn. Japan: The Dutch Experience. Bloomsbury Publishing, Dec. 17, 2013. isbn: 9781780934921. |

| Horiuchi, Annick. “When Science Develops outside State Patronage: Dutch Studies in Japan at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century”. In: Early Science and Medicine 8.2 (2003), pp. 148–172. issn: 1383-7427. |

| Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Akita ranga. Date accessed: 28.03.2017. 2001. |

| Kornicki, Peter F. The book in Japan: a cultural history from the beginnings to the nineteenth century. eng. Leiden [u.a.]: Brill, 1998. isbn: 978-90-04-10195-1. |

| Kuriyama, Shigehisa. “Paths to Asian Medical Knowledge”. In: ed. by Charles M. Leslie and Allan Young. University of California Press, June 11, 1992. Chap. Between Mind and Eye: Japanese Anatomy in the Eighteenth Century, pp. 21–43. isbn: 0520073185. |

| Low, M F. “Medical representations of the body in Japan: gender, class, and discourse in the eighteenth century”. English. In: Annals of Science 53 (1996), pp. 345–359. issn: 0003-3790 and 1464-505X. |

| Mestler, Gordon E. “A Galaxy of Old Japanese Medical Books with Miscellaneous Notes on Early Medicine in Japan Part I. Medical History and Biography. General Works. Anatomy. Physiology and Pharmacology”. In: Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 42.3 (July 1954), pp. 287–327. issn: 0025-7338. |

| Otori, Ranzaburo. “The Acceptance of Western Medicine in Japan”. In: Monumenta Nipponica 19.3/4 (1964), pp. 254–274. issn: 0027-0741. doi: 10.2307/2383172. |

| Rosner, Erhard. “Review of Kaitai Shinsho. The single most famous Japanese book of medicine & Geka Sōden. An early very important manuscript on surgery”. In: Sudhoffs Archiv 93.2 (2009), pp. 244–246. issn: 0039-4564. |

| Sachs, Michael. “Die „Anatomischen Tabellen“ (1722) des Johann Adam Kulmus (1689-1745): Ein Lehrbuch für die (wund-)ärztliche Ausbildung im deutschen Sprachraum und in Japan”. In: Sudhoffs Archiv 86.1 (2002), pp. 69–85. issn: 0039-4564. |

| Sakula, A. “Kaitai Shinsho: the historic Japanese translation of a Dutch anatomical text.” In: Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 78.7 (July 1985), pp. 582–587. issn: 0141-0768. |

| Santoni, Jean-Gabriel. “À propos du Kaitai Shinsho : éditions et traductions de l’ouvrage original”. In: Études de Langue et Littérature françaises de l’Université de Hiroshima 32 (2013), pp. 74–84. issn: 0287-3567. doi: http://doi.org/10.15027/35422. |

| Tinios, Ellis. “Art, Anatomy and Eroticism: The Human Body in Japanese Illustrated Books of the Edo Period, 1615-1868”. In: East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine 31 (2010), pp. 44–63. issn: 1562-918X. |

| Wagenseil, F. “Die drei ersten unter europäischem (holländischem) Einfluß entstandenen japanischen Anatomiebücher: Einleitung”. In: Sudhoffs Archiv für Geschichte der Medizin und der Naturwissenschaften 43.1 (1959), pp. 61–85. issn: 0365-2610. |